How we work, how we communicate and what we value is reflected in how we want to study. Teaching in higher education is determined, on the one side, by the expectations of each new generation, who explicitly value more and more cooperation, flexibility, transparency, freedom of choice and exciting challenges. On the other hand, higher education has for some time been in the grip of neoliberal tendencies that bring with them the expectation of an educational system that is, above all else, cost- and time-effective, standardised and measurable. In this current climate, what could the role of institutes of higher arts education (IHAE) be – how could they function as a safe and stimulating place for students and teachers alike? The following essay maps out the terrain and looks for possible answers. Some of the keywords are slow education, praise for mistakes and experimental methods.

Written by Maarin Ektermann,

Estonian Academy of Arts,

December 2021 – March 2022

“The traditional teacher-student relationship is changing, especially in view of the internet and the hyper availability of knowledge. […] I always ask students how they found information on the Internet, it is interesting because it is evolving all the time and even the students have very different ways of learning.”

Gabriel Rouet is working as a professional supporter in the SMAC 109 (label for music venues) and coordinator of the pop music department at the conservatory of Montluço. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 2nd of April 2021.

The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically, as Martin Luther King Jr said (King 1948). Education means expanding one’s horizons with new knowledge, skills and connections, and the possibilities of that seem nowadays to be abundantly out there. Various e-courses to take, online and offline lectures to attend, seminars to participate in, podcasts to listen to, articles and books to read – the amount of high-quality sources, often freely available, can make one’s head spin. Of course, this seemingly endless variety might actually not be so easy to access, as corporate-designed algorithms more often than not funnel information-hungry searchers into echo chambers.

“The digital world and how we access information is now a bit of a double-edged sword. Despite the available knowledge, we know that we are all locked into bubbles on the internet, and if there is no media education, especially on critical thinking, we will lock ourselves in even more. And a ready supply of seductive and conspiratorial information is also easily available.”

Gabriel Rouet is working as a professional supporter in the SMAC 109 (label for music venues) and coordinator of the pop music department at the conservatory of Montluço. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 2nd of April 2021.

The role of the teacher is to be one step ahead – to orientate us within this cacophonous landscape and to help us see what might be missing. Of course, it has always been like this, but now, with all this information available, it might appear at first that a teacher is not needed, that we can all educate ourselves. But to build something systematic out of this endless knowledge buffet, to build a “curriculum” for oneself, requires strong self-discipline and some life experience – getting overwhelmed and drowning in all that goodness is also very likely.

“We always try to seek the B-side. That is to say, not what students probably know from books or even from exhibitions, but what doesn’t appear anywhere. And that’s where I think the task of the teacher lies: in providing guideposts that normally students don’t know.”

Arantza Lauzirika is Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of the Basque Country and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 30th of April 2021.

Education is a slow system where changes take root ‘adagio‘ rather than ‘allegro’. But the teaching paradigm has changed a lot and seeing the teacher’s role as “pouring information into empty vessels” is now hopelessly outdated. Constructivist learning theories that prevail today emphasise an active approach from the learner’s side too, making use of their inner motivation in order to construct their own knowledge; learning happens through discoveries, and an educator’s role in this process is to support, facilitate and mentor (McLeod 2019). Especially in the midst of this information overflow, where our existing knowledge, skills and connections depend very much on previous learning paths that create a kaleidoscope of versions, getting to know your students and really, really listening to them might be the most important tool for a contemporary lecturer.

“We need to make our university colleagues understand that they are not supposed just to speak for themselves. They should come without knowing what they are going to say, because they don’t know who is going to be in their class and what the needs of the students in their class are going to be – they have to start by keeping quiet, being attentive to the needs of those students as well as their competences. What we are going to do together is to follow a variety of research, and we as teachers do what we can to accompany them, guide them, advise them and discuss with them; or, simply, be there attentively.”

Yves Citton is director of the University Research School ARTEC for Art, Digital technology Human mediation and Creation (Paris 8-Vincennes – St Denis) and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 26th of May 2021.

The generations labelled Y and Z, especially in European and North American societies, are typically confident, ambitious and with high expectations of their employers – and also of their teachers. They are sceptical of the status quo and value above all meaningful motivation (Kane 2019). Obeying an authorial voice is not an option, tasks must be reasonable, purposeful and exciting, and they are considered to be feedback-oriented and cooperative. Teachers, who are often from earlier generations, with different approaches to learning and teaching, have to recalibrate.

“What Arts Education have to provide to students are tools and from there let them do. And while they build, they can be provided with more tools, texts, references … so that they can continue building along the lines or issues they have chosen. In short, it’s important not to work with predetermined or closed objectives.”

Arantza Lauzirika is Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of the Basque Country and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 30th of April 2021.

In the arts there is an old debate around teaching – can art actually be taught? Or are some people just born with “it”? As art historian James Elkins points out, this goes back at least to Plato’s concept of inspiration – mania – and Aristotle’s concepts of genius and poetic rapture (the ecstaticos) (Elkins “Why Art Cannot…”).

Luckily, the modernist idea of the lone (suffering) genius is vanishing, and the veil of silence is dropping away, shedding more light on the hard work, luck and social norms that allow some artists to flourish, to become “geniuses”, while precluding others. With this paradigm change, some examples from the history of art schools are resurfacing: educational experiments like those of the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau, Germany (1919–1933) and Black Mountain College in North Carolina, US (1933–1957) are role models for flexible, communal and more horizontal art schools (Richter 2019).

Art does not belong solely to those who have a divine gift (which appears often to be constructed by context-specific privileges in any case, when looked at more closely).

Art can be taught, but perhaps not as a “banking model” – which, according to educator and philosopher Paulo Freire, is the situation where a teacher has all the power and “learning” means submitting to a teacher’s absolute authority (Rose 2017) – but rather through a co-creational or constructivist approach, that is by creating a joint learning environment where learning happens between student and teacher in both directions.

“I think it’s absolutely crucial that we work very closely with our students in a true partnership, in a true collaboration – it’s really important to involve students far more in the decisions we make. So, it’s more a collaboration rather than a top-down kind of approach to the co-creation of the future.”

Silke Lange is an Associate Dean for Learning, Teaching, and Enhancement at the University of the Arts, London and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 4th of May 2021.

“It is very important getting people [to IHAE] who are experts in these fields – and making sure that it’s not just old white men, but a diverse kind of speaker.”

At the time of the interview, Anna Eschenbacher studied the master’s program Creative Technologies at Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF in Germany. She was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 15th of March 2021.

Values are changing in society at large, not just in education. New generations are stepping into positions that determine who has the voice, whose experiences are heard, and those generations already have slightly different values from their parents (and often from their lecturers). Inclusiveness is becoming the new normal and, although many societies in recent years have encountered serious public debate concerning value questions, debates that often end up very polarised, the variety of voices is definitely greater than it was even ten years ago.

Also, institutes of higher arts education have to look critically at their ranks – Who has the power to shape the future of education? Whose voice is heard in academia?

“Who is teaching?

Who is creating the curricula?

How many persons of colour are teaching?

How many other people with non-dominant identities?

The subject position of the educator inevitably shapes the contents of teaching. The subjectivity of the educator has an impact on what they know, how they interpret society and history.”

Airi Triisberg is a freelance art worker, educator and activist currently based in Tallinn and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 30th of April 2021.

Those in power in IHAE Must Set an Example. Art education has developed out of strong hierarchies set in place in the 17th century Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in France, hierarchies that encompassed both artists themselves and genres of paintings.

As art historian Daniella Berman writes, “each professor selected students to be part of his studio and this is where artists actually learned to paint or sculpt by emulating their teacher, often contributing to his large-scale commissions” (Berman).

This, what might now be referred to as “guru-like teaching”, sets in place its own subjective, unwritten rules, selecting favourites and leaving no room for students’ own personalities, rhythms and wishes. This kind of authoritative teaching might well be accompanied by abuse of power.

Whether or not being a great artist is a mitigating factor with regard to unethical behaviour is a debate that is ongoing in the cultural sector at large (just to think of all the recent #MeToo cases). In the world of art, where professional and personal relationships are often hopelessly intertwined, careful and attentive eyes must also be kept on educational situations.

“Being a professor at a film school gives you a certain position, a privileged position, a position of power, because you realize sooner or later that students are really interested in what you’re saying and that it can have a huge impact on them. What you are saying, and in which way, can have a very specific impact, in a positive and in a negative way.”

Skadi Loist is a professor for production cultures in audio-visual media industries at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, researching with a focus i.a. on film festivals, gender equity and labour conditions.

“I can only set an example. And the most important example is how you yourself behave. How does this person called the teacher behave in this changing situation?”

Frieder Nake is a mathematician, computer scientist, researcher, and pioneer of computer art. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 20th of April 2021.

The values of the next generation are changing, but so too are their profiles as students. More students tend to work in parallel with their studies, and some have family responsibilities. People who already have a degree and expertise in one discipline may return to the educational system to get another degree and to expand their competences in another field.

The classroom becomes an encounter with different generations, with those with different life and work experiences, and in order to accommodate those expectations much greater flexibility is needed. Borders between creative fields, departments and curricula are starting to feel like obstacles.

“It should be noted that, in most IHAE, a diversity of practices is present, but that there is a very strong tendency to compartmentalise, preventing circulation between them, so that each one stays in its own particular corner.”

Jean-Charles François is part of the PaaLabRes artist collective based in France. PaaLabRes was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of May 2021.

“I do think that there are university study models or projects that are very interesting, which try to cross disciplines and methodologies that not only encompass the arts, but also, technology, science… And for me that’s the goal that institutes and universities have aim for in the coming years. That ability to cross curricula, to move from one field to another… It is happening in some way, and I think it is very important that it continues to happen, and that it happens more often.”

Tere Badia is the Secretary-General of Culture Action Europe, a European network of cultural networks, organisations, artists, activists, academics and policymakers. Tere Badia was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of April 2021.

Students who bring with them a strong desire to decide for themselves demand an even more individualistic approach.

Although art schools have always championed a personal approach, and working in small groups, there is growing demand to move even further in this direction, especially as we can now see the new shape that work-life is taking – working remotely, freelance-based etc.

This correlates very much with the operational logic of the contemporary art field, which is heavily project-based, since artists are commissioned to contribute to different exhibitions and festivals all over the globe. So there are expectations that education must develop according to the same logic.

“I imagine future institutes of higher arts education to be hybrid spaces where everyone can log in virtually from everywhere and then share a creative learning environment with others. In this space, people will be more physically present than today, because telecommunications will be very different in these times to come. At the same time, the possibility of physical presence has to be maintained. To be present in school, interacting with each other with all your senses and working on practical things on site. For example, working on a sculpture requires all the tools provided by the university.”

Marcel Bückner is a visual artist and part of the studio for audio-visual art Xenorama, based in Germany. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed him on the 17th of March 2021.

This vision of an art school that would dematerialise/ materialise according to each student’s needs has of course some pitfalls. Working and studying worldwide is related to many privileges. Time zones still exist, which hinders this illusion of being locationless. Hopping from project to project, from location to location or from job to job in the gig economy is not a sustainable practice and contributes to the already boundless ranks of a precarious workforce.

But, taking all those potential traps into account, the changed profile of art school students does mean that more flexibility to combine their studies with work/family obligations is in order.

Flexibility. Diversity. Co-creation.

Those are the keywords when talking about the hopes and wishes related to higher arts education.

But in order to understand the possibilities for their greater realisation within the contemporary art school we have to look at the processes that are currently shaping higher education in general.

Looked at more widely, it’s evident that recent decades have seen a neoliberal influence on education, according to which it should operate by the logic of efficiency. The rationalisation of the work of universities, questioning the “usefulness” of higher education, especially arts and humanities, the constant reduction in state subsidies, the application of the vocabulary and criteria of business and industry – all this affects the autonomous position of universities and the opportunity to focus on research/teaching practices that cannot demonstrate results in the short-term.

Pascal Gielen and Paul De Bruyne, editors for the Valiz Antennae series that identifies new lines of thought in the arts, argue that academies and universities are expected to deliver knowledge that is made-to-measure, saying ironically that: “Education has indeed become a form of catering, and just like in catering, the client is well aware in advance of what to expect, which is never the sublime cuisine of a top-notch restaurant, but a well-calculated mediocrity” (Gielen, De Bruyne 2012:3).

Although this neoliberal climate is present within higher education at an almost global level, there are different focal points in critical discussions in Europe and in North America:

In the US raised tuition fees, the decrease of federal subsidies and the rise of for-profit colleges push students towards loan-dependent educational paths. This has a strong influence on the choice of what to study, and on mental health while studying. This situation has been declared a student loan crisis and means that after graduating people are burdened with dreadful levels of debt that go on to mark their options for years, as they delay traditional markers of adulthood such as having kids or buying a home (Hess 2020).

In the European Union the Bologna Agreement is usually the focus when debating the changed ethos of higher education. This treaty, signed by the ministers of education of all the European member states in 1999, can be regarded as the official starting point of the neoliberalisation of education (Gielen and De Bruyne 2012, 7). The Bologna directives standardised higher education into a formula of three-year bachelor and two-year master degrees, followed by what seems like compulsory doctoral studies. There are definitely upsides to the Bologna Agreement, such as the possibility of continuing study anywhere in Europe due to the unified ECTS system, travel funds provided for students and teachers through programmes like Erasmus and Erasmus+ and so on; but, overall, problematic issues prevail, such as the rise of bureaucracy, the pressure to make the educational system more frugal, and an orientation towards measurable results. All these aspects compromise the feeling of freedom usually associated with studying/teaching in higher education.

“We live in a society here in Europe where efficiency, monetary terms and accessibility prevail. It is all quantified in numbers. Statistics galore. But how do we measure how something feels or how it affects us? How do we measure what art achieves? I’m sometimes amused by all these numbers, like how many participants attended this and that event – I think what is significant is how it affected those people experiencing it!”

For lecturers in institutes of higher arts education (IHAE) working in the current climate of efficiency, this provides several challenges. One of the biggest ones: the “full-time lecturer”, as such, has become a rare species. As in higher education generally, in IHAE there is a tendency to rely increasingly on temporary or non-tenured teachers – low-paying, precarious jobs with no social guarantees. With this kind of structure, significant savings are achieved with regard to teaching, but it means the erosion of the school’s community. Coming in just to teach one course is often not enough to get a sense of the school itself and to develop sustainable relationships with students, especially when the meeting time is precisely scheduled, calculated and contracted.

Numbers – this is the focus of the most heated discussions between colleagues now in academia.

How many meetings?

How many working hours?

How many contact hours?

How many learning outcomes?

How many participants in one course? (Often, so, so many!)

How many are evaluated?

How many As?

How many Ds?

How many graduated?

How many quit?

How long is your to-do list?

“Whenever you start to institutionalise things it has a tendency to become bureaucratic. Especially all these questions of grading in the arts are more or less completely senseless. In my observation, they tend to become way too important from the student’s perspective. Instead of giving precise feedback about artistic development, it is all suddenly put into numbers, which don’t say much, but create an illusion of ‘oh, I’m good’ or ‘oh, I’m so bad’. Art is a bit more complex than that.”

“What I am missing is space and time for students to learn about other strands of thinking. These strands of thinking maybe come from other disciplines.”

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Kropp is the deputy chair of the Department of Climate Resilience at PIK (Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research), and head of the Urban Transformation Research group (PIK). He holds a professorship for Climate Change and Sustainable Development at the University of Potsdam. The interview was conducted by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 14th of April 2021.

High tuition fees and a competitive atmosphere, the constant need to prove yourself worthy, even before stepping into professional life, increasingly shape students into clients and academic personnel into service providers – into “catering service”, as Gielen and De Bruyne (2012) diagnosed. Most of the time, the results of the learning process must be instantly visible, instantly useful, instantly understood. Education is expected to become a concrete toolbox, not a potential toolbox.

“Looking at nearly 20 years that I’ve been teaching, the Bologna Process has made it a lot harder, because the official time where you’re supposed to do a BA in three years and a MA in two years. This allows for very little time to adapt to the institution, to understand what you’re actually doing and then to look beyond that. Students nowadays have a harder time of just trying to get through the curriculum, being able to navigate it and find their own ways. My own experience was studying five to seven years in one place, the trajectory was a lot longer and you had more time to find your own way. This is the nice part of studying, not feeling pressured to get through very quickly and get into the market. So, I feel like the structures make it more difficult and also the way societal or industry expectations are framed, which might also have an impact.”

Skadi Loist is a professor for production cultures in audio-visual media industries at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, researching with a focus i.a. on film festivals, gender equity and labour conditions. Skadi Loist was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 20th of May 2021.

Dean Kenning, artist and writer, has pointed out how business/entrepreneurial rhetoric has infiltrated curricula, placing a high value on “positivity”, presenting oneself as cheerful, cooperative and non-antagonistic while discouraging “negative” manifestations like doubt, difficulty, subversion, estrangement, awkwardness, resistance and paradox – traits that many art education courses still hold in high regard in order to connect subjective states to wider social concerns (Kenning 2019).

Another aspect influencing studying experience in higher education and in IHAE is the heavily (and expensively) produced entertainment industry that surrounds us 24/7 and does an excellent job of wrapping information in colourful bite-size pieces that are easy to digest – so that one starts to expect this from all spheres of life. Generation Z has already been identified as one with cognitive impatience, which Marianne Wolf, scholar and teacher, describes as a worrying tendency, an “inability to read with the sophistication necessary to grasp the complexity of thought and argument found in denser, longer, more demanding texts, whether in literature and science classes or, later, in wills, contracts, and public referenda” (Wolf 2019).

Universities and academies are in an involuntary competition in which they appear old-fashioned and boring. But the problem is not only about readiness to dig into Fyodor Dostoyevsky for your literature class, but about reading small print in various contexts!

Taking into consideration neoliberal educational policies towards higher education and the influence of the ceaselessly active entertainment industry… How can institutes of higher arts education respond to expectations described in the former?

The expectations about teaching in IHAE described above collide with the tendencies within higher education that have been introduced by neoliberal processes – flexibility is compromised by increased bureaucracy, the changing role of the teacher clashes with the pressure of budget cuts and full-time positions are replaced with short-contract ones. Amid this turbulence, art schools seem to have a bit more freedom than universities – so, is there perhaps a chance to take a stand for values that seem to be getting pushed aside within higher education?

“Institutions of higher education of the arts should be obligated to make a criticism of the current world, to enable people to build alternatives – and to be themselves alternatives to students’ experiences.”

Nicolas Sidoroff is part of the PaaLabRes artist collective based in France. PaaLabRes was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of May 2021.

One of the main skills that artists have, and the way in which they contribute to society, is the ability to pay attention, in a concentrated and critical manner, to the everyday situations surrounding us, and to then reflect on and analyse what can otherwise go unnoticed or be regarded as trivial, as something that has “always been so.”

“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable”, a quote from a religious context that has become known in the 20th century through poet and activist Cesar A. Cruz (Cruz 1997) and, most recently, through the works of street artist Banksy, provides one outstanding motto with which to describe an artist’s role in society. Paying acute attention, with their antennas perpetually tuned in, artists, in return, create new perspectives, new experiences through their work.

This role – swimming against the mainstream – could also be celebrated more boldly in IHAE. People who find their way into those institutions, who want to study and teach there, have already recognised in themselves the need to find alternatives, to do something different, to follow their calling rather than a predetermined career path or a life based on rational cost-efficient choices.

“If you are going for higher arts education or higher education in general, you are willing to learn. We have to open up opportunities for students to learn, we don’t have to restrict their learning, we don’t have to push them with many deadlines and we don’t have to force them to go through fixed curricula.”

Marcel Bückner is a visual artist and part of the studio for audio-visual art Xenorama, based in Germany. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marcel Bückner on the 17th of March 2021.

Being filled with people who are highly motivated and willing to think outside the box should already give IHAE the courage to experiment more adventurously with its approaches and to stand for certain values.

“For me, any school – and in particular a higher education art school – should be responsible for an ecology of practices, for the existence of a diversity of practices, so that the students, when they leave that school, can choose their own artistic practices, their own ways of doing things. Not the discipline ‘music’ or ‘music with circus’ or ‘music with circus in a particular way’, but a way of doing, a way of experimenting, a way of fabricating. And in order to give them that we have to allow them to experiment in a ‘secure’, comfortable framework in which one can fail – failure should even be welcomed because it allows reflection. So, a higher education art school should be safeguarding the ecology of practices, but it seems to me that things that are done on the periphery, that never reinterpret the centre, are more and more in danger.”

Nicolas Sidoroff is part of the PaaLabRes artist collective based in France. PaaLabRes was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of May 2021.

One thing that seems to be missing in today’s educational ethos is leaving adequate room for mistakes – often, there is not enough time for wrong turns, cul-de-sac, for starting over. Delays in predetermined study plans result in falling behind, which involves a lot of stress in rescheduling the many parties involved and, in some cases, extra cost for ECTS. IHAE has taken over the project-based logic of the contemporary culture industry, which demands new ventures and new outcomes all the time, each one better than the previous. Project-based learning means that the curriculum is divided into beginnings and endings. For example, one of the most popular formats nowadays in IHAE, the workshop, must end with results presented, defended and evaluated. But what if one can’t switch over that quickly from project to project, jumping between workshops? What if carving out the idea takes longer than a predetermined timetable allows?

“… you have the old art school idea that you’re in a secure realm where you have the time to create something or you have the luxury to just experiment and it doesn’t have to be profitable in the end. You can also fail – that’s an important part right here! You have the time, space, finances and infrastructure to experiment and see what could be done differently, and you do not have to get it right immediately.”

Skadi Loist is a professor for production cultures in audio-visual media industries at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, researching with a focus i.a. on film festivals, gender equity and labour conditions.

Could we come across this “old art school idea” more often nowadays? How might one integrate mistakes back into the curricula and create an art school as a safe space in an accelerating world? One important step would be to talk about it more! And to admit openly to students that even seasoned practitioners like professors have made many mistakes throughout their careers, and continue to do so. That behind every vernissage, premiere or project launch are numerous wrong turns, dead ends, failed testings – moments when one is lost and overwhelmed!

“There are these start-up nights where people present their successful start-ups, but there are also fuck-up nights where people present their failed start-ups – and presenting how their idea didn’t work or what went wrong is super-beneficial!”

At the time of the interview Anna Eschenbacher was studying the master’s program Creative Technologies at Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF in Germany. She was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 15th of March 2021.

Experimenting, making mistakes, and, more importantly, learning from them, digesting them, going back to the research phase takes time – and is hard to understand when looked at from the outside. Pressure on the arts to be more “useful”, specifically measurably useful, is also one of the characteristics of a neoliberal climate.

“Especially in arts education, it is important to have a dialogue [with the industry]. Both sides can learn from it. … However, I don’t think that everything in arts education should focus on the industry. Of course, in education, you need artistic freedom and possibilities to experiment and to learn things that do necessarily have an immediate practical value.”

Benjamin Benedict is the Head of High End Drama and CEO of the production company UFA Fiction GmbH. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 19th of April 2021.

So – celebrate blunders, missteps, slip-ups, misestimations, errors, flaws, fallacies, confusion, aberrations, lapses, miscalculations, inaccuracies, oversights, faults, muddle, bewilderment, perplexity, haziness, puzzlement, bafflement, and do so more, and more fully, in IHAE and there would be the possibility of creating a healthier, more emancipated and propulsive learning environment.

“Learning happens through interaction. It happens through conversations and disputes. And also maybe sometimes through the experience of being challenged, the experience of growing together with someone. I think a lot of learning happens through conflict or through kind of friction, for which you need contact, continuous contact.”

Airi Triisberg is a freelance art worker, educator and activist currently based in Tallinn and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 30th of April 2021.

Making mistakes is just half the story – learning from them is what really matters. One major advantage that attending an art school can offer in comparison with a DIY educational path is in providing a peer group, such as lecturers or visiting experts, but also classmates, students from other departments etc. Art schools have traditionally had smaller groups and a more personalised approach than many other fields in higher education. This is a valuable characteristic for IHAE, enabling a student-centred approach and allowing for the cultivation of more horizontal relationships organically.

“We try to have smaller groups, which helps for conversations to develop – otherwise, what students often do in seminars is that they delegate the work of talking to a few students who like to speak and that dynamic is then very hard to be broken.”

Airi Triisberg is a freelance art worker, educator and activist currently based in Tallinn and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 30th of April 2021.

Giving feedback on students’ work might be a tricky issue when teaching in IHAE. There are technical and medium-specific competences that can be effectively evaluated, but how does one evaluate that this piece “convinces”, that “it works”? That it has sufficient balance between the conceptual and the way it is executed, between content and form? Isn’t it a very subjective assessment? It definitely needs the expertise of a seasoned practitioner – but doesn’t that already mean deploying an authoritarian voice?

Creative practice pedagogies researcher Susan Orr points out that art and design lecturers often work together to mark students’ work, and that is one key aspect defining the pedagogy in IHAE. Orr says that “the fact that group approaches to marking have remained a central tenet of art and design assessment in the face of massification and the intensification of lecturers’ workloads underlines its importance” (Orr “Making marks…”). Assessments happen then in dialogue and the possibility of different voices enables feedback from multiple angles. Of course, if opinions diverge a great deal, this might be confusing for a student, but it is the responsibility of the evaluators to keep a constructive tone.

Facilitating the learning process does not only require being a great artist, with lots of experience in the field, but necessitates learning new skills as a lecturer too. Traditionally, this pans out over time, as particular personal characteristics that might lead someone to consider teaching converge with methods learned from general, introductory pedagogical courses, but in the main, it tends to happen in a learning-by-doing manner. Given that current neoliberal influences within higher education have reduced in-house academic staff numbers, and that IHAE also relies more on non-permanent lecturers, educating the educators has become an important factor.

“Maybe what we are teaching is not so outdated, but the way we teach is becoming outdated? Very often we still assume that when you are a good practitioner you’re also a good teacher.”

Eik Hermann is a lecturer of practice-based theory and philosophy at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) and Co-Editor-in-Chief of the architecture magazine “Ehituskunst”. Eik Hermann was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 6th of May 2021.

Supporting experts who find themselves in pedagogical situations, in front of a classroom or heading a workshop, requires renewed attention from the institution, a toolbox prepared and available for use in a flexible way. In the Estonian Academy of Arts, for example, there are, as well as the annual course “Introduction to teaching”, monthly seminars – open to in-house staff and temporary lecturers alike – that concentrate on different topics (evaluation and feedback practices, how to offer support on mental health issues, solving conflict etc.), a monthly newsletter with articles, interviews and events, online resources of pedagogical methods, and, last but not least, teaching consultations.

This seems to be quite a good mixture of formats in terms of offering support to teaching staff from various backgrounds.

“Time and exponentiality are capitalist technologies that make sure you don’t have time to reflect or to study.”

Jaime de Los Ríos is an artist, curator and specialist in new media and new technologies currently based in Spain. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 21st of May 2021.

Most institutes of higher arts education (IHAE) have supporting programmes for young teachers, courses on basic pedagogy etc., but can we go beyond that, find new ways to structure the increasing workload and to create more solidarity among colleagues?

Taking one’s time might be the most radical experiment to take on in higher education. If the principal trend is to accelerate, both in education and in society in general, then slowing down could create powerful disruption. Slow food (with its manifesto in 1989), slow fashion and other similar movements are associated with more sustainable ways of living, and with better mental health, a better quality of life. What could slow education mean?

“If you think first about fast education, the idea is to get these students through the process as efficiently as possible, to give them the necessary skills to become whatever society wants them to be, one tiny bit in the overall system. It’s not asking what the student needs, what their peculiarity is, their tempo – it only asks what we want them to do. I think IHAEs would be the best place to implement another kind of vision, a vision of slow education. It’s a good fit with the students that these kinds of institutions attract.”

Eik Hermann is a lecturer of practice-based theory and philosophy at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) and Co-Editor-in-Chief of the architecture magazine “Ehituskunst”. Erik Hermann was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 6th of May 2021.

Education researcher Ieva Margeviča-Grinberga has pointed out that the main elements in slow education are mindfulness, being present, following one’s “natural time”, focusing on process instead of results, and being deeply connected to one’s environment – physical, but also mental, in relation to the immediate learning community as well as to wider society (Margeviča-Grinberga 2021).

One inspiring source on this topic is a book by seasoned academics, professors Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber: “The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy”, which focuses especially on the experiences of the teachers-researchers, something that seems to be left to one side in the course of recognising the stress of students (Berg and Seeber 2017, 6). Their proposal is to dismantle the current attitude in academia that praises working like a machine, vigorous time planning, effectiveness, and quantifiable, profitable goals, and the like. Such values should be replaced (or at least balanced) with those inspired by slow movement: setting healthy boundaries, taking regular sessions of timeless time, promoting the pedagogy of pleasure, taking time to support one’s colleagues, even developing an alternative vocabulary about how to address our experiences in academies (Berg and Seeber 2017). As the authors say: “Slowing down is about asserting the importance of contemplation, connectedness, fruition, and complexity. It gives meaning to letting research take the time it needs to ripen and makes it easier to resist the pressure to be faster. It gives meaning to thinking about scholarship as a community, not a competition. It gives meaning to periods of rest, an understanding that research does not run like a mechanism; there are rhythms, which include pauses and periods that may seem unproductive” (Berg and Seeber 2017, 57). Here the authors use research as an example, but they point out that the same holds for teaching/learning as well.

The revolution envisioned by Berg and Seeber inside academia starts first of all with being more honest with oneself, and then being more honest with colleagues/students, not keeping up appearances all the time, not praising only those moments that are successful, but allowing oneself to be seen as struggling, as needing a break, as taking more time. Constructing a safe environment for students and lecturers alike should be the task of every institute of higher arts education and creating an alternative to the usual way of doing things should be seen as a badge of honour.

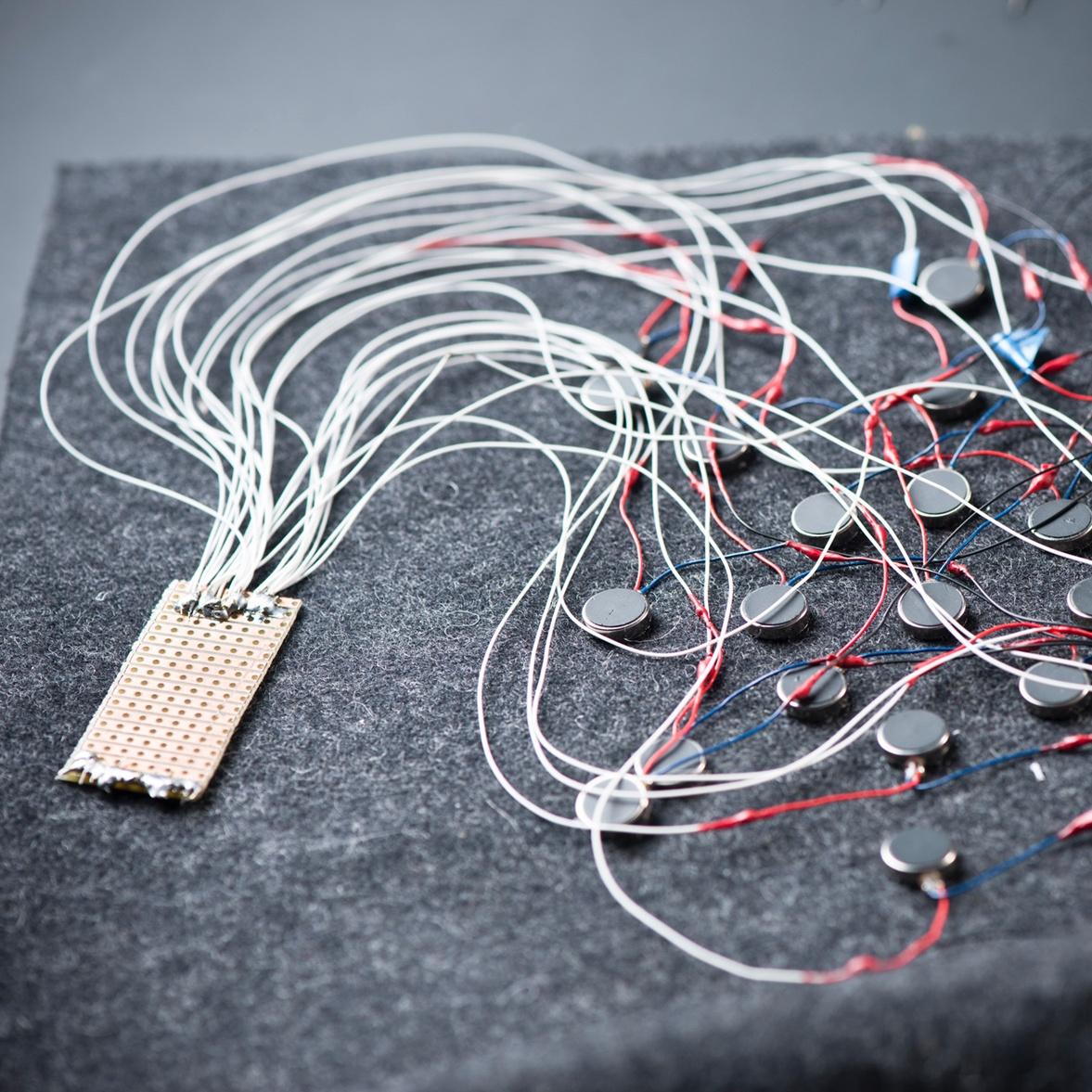

One of the ways in which art schools can create a safe space for experimentation is through the mental environment – by honouring values such as slowing down, learning from mistakes, by colleagues and students supporting one another rather than competing, by paying attention to power relations etc. But the physical environment in which education takes place has to support the same ethos.

Every institute of higher arts education negotiates daily, in its physical space, in order to achieve a balance between order, cleanliness and control on the one hand, and, on the other, an environment in which to be loose and messy in the service of the creative process. Administration on the one side, students on the other. Traditionally, art schools (as artists’ studios) have been seen as laboratories, where layers of materials, left-overs, bric-a-brac and ideas grow and procreate, but next to those spaces, art schools have classrooms for history and theory subjects that look more like… well, more like offices.

“Education in the Western world is still in the grips of a distinction between mind and body. This distinction should be questioned also on the level of teaching. We’re still assuming that these things are separate, so we can teach the soul while the body is just sitting there.”

Eik Hermann is a lecturer of practice-based theory and philosophy at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) and Co-Editor-in-Chief of the architecture magazine “Ehituskunst”. Erik Hermann was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 6th of May 2021.

General classrooms in art schools do not have to look like offices in the IT sector – with swings and soft chairs, heavily decorated with photo wallpaper. Even allowing students to do something with their hands, like doodling or shaping a material, while they listen to an art history class, for example, might result in better concentration. Bringing your art practice with you as you work through different courses can be a win-win situation (keeping the focus on the main task at hand, of course).

Next to studios and general classrooms are areas where “ideas can have sex”, as author and columnist Matt Ridley said in his famous TED talk (Ridley 2010). To put it in a less giddy way, these are the areas where people meet or bump into one another, and they are as vital in an art school as private and quiet spaces.

“I think one of the most important factors in a learning environment is the balance between having space to oneself, in order to concentrate on one’s own art, but also a space in which to encounter others, with a whole variety of people!”

Designing a lively meeting spot is as hard as hosting a good party – you can predict and nudge people’s behaviour, but often undetectable “it-factors” determine which cafeterias will be social hotspots and incubators. Nevertheless, keep on trying, institutions of higher art education, you can’t do without it! Art school should be a living organism, a flexible space where it is possible to balance social/individual time for yourself and time spent together.

“I think IHAE really needs to be a place that is alive. We need places for visual work and workshops, that is clear, but also places for non-productive meetings; it could be a kitchen or another type of space for discussions and informal meetings. And as well as that, an exterior space, a garden, rooms with lots of light, big windows. Flexibility in terms of furniture, which could change place and function. Walls to hang things …”

Marie Preston is a teacher-researcher and associate professor at the visual arts department of the University of Paris 8. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marie Preston on the 29th of April 2021.

Nowadays it is easy to think that the best art school is the one that has the greatest number of 3D printers and other cutting-edge equipment for students. But these are just tools that become useful when offered in the right mix with other things of value.

“Resources in many contemporary IHAE are fantastic and provide opportunities to explore and to hone one’s skills in particular ways, but I think this aspect is sometimes over-emphasised. You step into a different context in a different part of the world and engage with artists who have very limited resources, just to see how creative they can be with the resources they have, how they develop their skills and their artistic thinking. This puts things in perspective – we are here in a very privileged position and that sometimes goes against what we’re trying to develop in our future artists.”

“One direction for contemporary IHAE might be to look for ties beyond the disciplines usually designated creative!”

Eik Hermann is a lecturer of practice-based theory and philosophy at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) and Co-Editor-in-Chief of the architecture magazine “Ehituskunst”. Erik Hermann was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 6th of May 2021.

Writer and urban theorist Andy Merrifield points out in his book “The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love” that our current age is defined by experts and professionalisation (Merrifield 2017). One thing this has brought with it is a narrowed sense of the possibilities when it comes to participating even in democratic processes – it is getting too hard, without specialist training, to understand what the discussion is about! Also, in the arts and culture sector, professionalisation already happens at a very early stage – pressure to develop your brand, communicating this constantly through different channels, being efficient in self-management, and producing a constant flow of new works. Complying with high standards means retaining an intense focus, with no time to mess around. It also tends to mean working deep in your own trench, something that now starts to develop at a very early stage, even while studying in IHAE.

“I think sometimes we are looking in too narrow boxes at the ways in which artists are trained, the kinds of skills that they tend to focus on during their education. This really needs to be re-thought and broken apart, in terms of those boxes that have been there in the past.”

How to encourage meetings between different disciplines before students dive into their own compartments? Transdisciplinarity has become quite a buzzword, but it needs special attention, a continuous and conscious approach that moves towards mixing and matching.

“In the future there should be more art schools with a transdisciplinary nature – a greater number of different projects with different people from all walks of life, plumbers, urbanists, crafts people, other disciplines, making new links and testing those links. Many of those new links will not work. In fact, most of them won’t work. But some of them will. The whole goal of it is to raise the likelihood of finding those spots where different domains interact with each other. And if some of those interactions work, even if two people meet and become friends, hang out and do something together, that’s a win.”

Marten Kaevats is an architect, urban planner, and community activist, at the time of the interview he worked as Estonia’s National Digital Advisor. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marten Kaevats on the 7th of May 2021. Marten Kaevats is an architect, urban planner, and community activist, at the time of the interview he worked as Estonia’s National Digital Advisor. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marten Kaevats on the 7th of May 2021.

Delaying specialisation and creating a variety of connection points with people from different walks of life should be enhanced in the course of studying. One superpower the artist could develop is that of the in-between, a kind of “glue” that brings different parties into dialogue (and towards action). Architect, consultant and writer Markus Miessen has called this kind of practitioner “a crossbencher” and explains: “This role entails that in a given context one neither belongs to nor aligns with a specific party or set of stakeholders, but can openly act without having to respond to a pre-supposed set of protocols or consensual arrangements” (Bueti 2013). We need translators between disciplines, and artists, with their capacity for attention and reflection, are perfect for this task. Of course, being in-between is not always an easy position to be in.

“It should actually be addressed more, during one’s studies, how to be in-between, how to communicate your knowledge and know-how to different parties. It’s also super complicated, because your position in the middle takes a lot of time to develop and it takes time to convince other people that there is value in what you’re saying.”

Jiří Tintěra is an architect, municipality architect, and senior lecturer at Tallinn University of Technology. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 27th of April 2021.

Teaching in IHAE is strongly influenced by the neoliberal tendencies that have shaped higher education now for decades. It is easy to see how these tendencies have complicated things, especially for teaching in the arts, and dissatisfaction and criticism have been voiced by both students and lecturers/ researchers. Imagining the future for teaching and learning in IHAE, one would hope that it could stand even more proudly for values such as experimentation, complexity, taking time and re-defining “usefulness” in its words and deeds. Instead of trying to stay on top of your to-do list, maybe you should prioritise your ta-da list?

“In the utopian future of IHAE I see it as having a different relationship to time; there is less stress and less focus on productivity, in terms of always producing more than we need. There is a relationship to space with soft mobility. All courses would be open to all. There would be workshops, spaces where there would be no problems with theft, where the doors would be open, school in general would be open day and night… There would be vegetable gardens run by students and university staff. The whole school would be self-managed. I know that life would not be all green and sunny, but we can hope a little!”

Marie Preston is a teacher-researcher and associate professor at the visual arts department of the University of Paris 8. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marie Preston on the 29th of April 2021. Marie Preston is a teacher-researcher and associate professor at the visual arts department of the University of Paris 8. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marie Preston on the 29th of April 2021.

Dive into the research

Merrifield, Andy. 2017. The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love. London ; New York: Verso.

Discussion

No feedback has been added yet

Share a Thought