In a context of continuous transformation of economical logics, the world of culture must be seen as a source of development not only through the introduction of symbolic values but also by reinforcing its capacity for innovation in society, by contributing with new attitudes and values that transform the perception of value, which is central in economics. This fact becomes a window of opportunity to connect the world of arts and culture with the world of organizations, transcending the classical links and moving towards a new relational framework in which to learn from each other, create shared knowledge, catalyze creative capacities and promote new processes of transdisciplinarity. The arts, culture and creativity have become key factors of economic and social transformation under the prism of social innovation.

How are we going to train artists to enable them to be catalysts of change through their skills and abilities and through new methodologies of co-creation and cross-fertilization?

Written by Conexiones Improbables, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain 2022

Societies operate in economic, social and technological interrelated contexts which are undergoing a continuous evolution that has been subject to a progressive acceleration. An evolving environment of economical logics and models that has moved from a productive economy that ruled much of the 20th century, giving way to a service economy, and from this to a knowledge economy. In more recent decades, the so-called economy of experience (Pine & Gilmore, 1999) has been further explored, understood as the one that forces organizations to move from being producers of goods and providers of services, to having a broader purpose linked to the generation of memorable events and meanings, new relationships and connections and, especially, experiences. Economy of experience has the arts, culture and creativity as key factors of transformation, making it a creative economy.

Although there are different stages in the development of the Creative Economy, the origin of this concept is traditionally located in the work of John Howkins “The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas” (2001), where he focuses on the ability to generate economic value from the marketing of products or services based on creativity. He understands that not all creative activity generates economic activity, but that there is certain specificity in creative-based economic activities.

Three stages in the life of the creative economy (Andy C Pratt, British Council)

Nowadays, the shift to the dominance of the discourses surrounding Cultural and Creative Industries seem to have displaced culture and creativity, the main components of the Creative Economy, putting a larger emphasis on its industrial dimension, linked to the idea of exploitation of the intellectual and industrial property. Despite the fact that cultural and creative industries make a significant contribution to the world economy, playing a crucial role in fostering innovation and creating new models of work and business, this discursive dominance has become both a conceptual and practical obstacle to think afresh about culture and the complexity of cultural work in the digital age (Gómez de la Iglesia, 2019).

Creative Economy Report 2013 (United Nations)

This paradigm shift in the the creation and distribution of value doesn‘t imply a radical transformation that makes us leave previous practices and models of thought, but rather encourages a sometimes tense coexistence between old and new paradigms: tradition and modernity, tangibility and intangibility, consumption, use or experience, individualism or collaboration, personalisation or standardisation… The progressive intangibilisation of the economy has meant that the main focus of governmental bodies and the private sector is nowadays on digitalisation. Alongside, its valuable contribution to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals – despite the low relevance of this dimension in the 2030 Agenda’s approach- and the importance of creativity, that emerges as a third key factor of development and progress.

Culture on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda (VVA, 2019)

Beyond the economical impact of cultural and creative industries, the creative economy is also about making all social and economic sectors more creative and innovative. Here, the focus can be placed on how to boost the creative sectors (without forgetting that the core lies on artists and creators) and on how to make other sectors more creative (and what role cultural agents should play): “Cultural and Creative Industries can be considered as a very dynamic sector and the expectations are high that this development will remain positive in the next years as companies and organisations initiate new forms of work (i.e. use of collaborative and cocreative working methods), incorporate digitalisation by the application and the use of new technologies with a strong service orientation, operate in a dynamic innovation environment and initiate spill over and transversal innovation effects in a variety of economic industries and societal levels” (Austrian Institute of SME and VVA Europe, 2016).

“For me working from the arts and as an art professional with other sectors and fields of knowledge, is one of the most interesting areas to develop and implement. There are things being done and more transdisciplinary projects are being implemented. I like to call them in-disciplinary. When everybody is willing to give up their discipline’s positions of power – not the discipline itself but its position of power- to work together, I think that’s fundamental.”

Tere Badia is the Secretary-General of Culture Action Europe, a European network of cultural networks, organisations, artists, activists, academics and policymakers. Tere Badia was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of April 2021.

“There’s an important question, which is to bring art, culture and creation to have a different, yet specific, weight in the public sphere that I think they presently lack. In other words, they don’t engage in the general discussion and it is a space we have to fight for.”

Clara Montero is the Cultural Director at Tabakalera International Centre for Contemporary Culture in San Sébastian, Spain and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 3rd of June 2021.

As the world of arts, culture and creativity is the great expert in generating experiences, its impact on the set of practices and behaviours should become crucial in the change and development of social and economic spheres. The approach and nature of innovation required by the shift towards the experience economy demands the constant creation of new knowledge within and between organizations and above all, together with the assimilation of earlier models, involves the adoption of new values, mostly cultural, within the framework of social innovation, a kind of innovation responsible and value-driven.

So, beyond the relevance of culture as an economic sector, its weight in GDP, in the generation of direct and indirect employment or positive externalities in a territory, the most relevant dimension of the relationship between economy and culture lies in the concept of value, which is central in economy. It is a society’s set of values that shape its citizens’ idea of value. In other words, working on the transformation of values, something that culture and art does or should do, means working on the transformation of the economy (Groys, 2005).

“Art has the soft power of changing viewpoints, it can influence our ways of relating to other human beings or the environment around us.”

Airi Triisberg is a freelance art worker, educator and activist currently based in Tallinn and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 30th of April 2021.

Despite these assertions, we must not fall into a good-natured vision of the role played by the arts and culture in the construction of society, since per se they don’t guarantee the emergence or consolidation of “civilised” values. We run the risk of culture being hijacked by those who only seek to instrumentalise it to reinforce an unsustainable development model. But given the rise of its symbolic value, we also have the opportunity to enrich it conceptually and in practice, by diving into dialogue with other disciplines, with diverse people who see reality in a different way, gathering diverse concerns and responses, reworking them… to lead a necessary strategy of cultural change, the emergence of new values and citizen experiences.

“Art can have a substantial impact with formulating complex positions, opening doors to new thinking, and connecting people with different points of view on the same topic. The arts are a great catalyst for forming discussions in society.”

Susanne Stürmer is the president of Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF in Germany. She was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 14th of April 2021.

So to speak, generate an economy of experience underpinned by new practices and values, where creativity is central in order to move from contexts characterised by the sectors with the greatest productive weight (industry, services…) towards others characterised by creativity permeating all sectors: “in a recent variant of creative economy thinking, some argue that the cultural and creative industries not only drive growth through the creation of value, but have also become key elements of the innovation system of the entire economy. According to this viewpoint, their primary significance stems not only from the contribution of creative industries to economic value, but also from the ways in which they stimulate the emergence of new ideas or technologies, and the processes of transformative change” (UNESCO 2013, 21).

“An artist is precisely the one who opens a gap, so to speak, an epistemological gap in society. That is to say, a musing gap that is not there, of contemplation, of philosophy… It can be done stemming from any discipline. It is a characteristic of art that other practices do not have. For me, art must be constructivist in the sense that it allows to create people, and that those people build society. It is a cybernetic system. You can use art to express the injustices of life, but with the freedom to criticize any kind of injustice. Art is precisely an issue that is neither politics, nor engineering itself, and it is also very important for society because it works originating from the transdisciplinary. Then the most important thing about art is no longer there, which is the ability to reflect and to destroy itself in order to rebuild once more.”

Jaime de Los Ríos is an artist, curator and specialist in new media and new technologies currently based in Spain. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 21st of May 2021.

Innovation models have evolved in parallel with the evolution of economic models. From purely productive innovation to scientific-technological innovation, currently slowly moving towards the idea of social innovation, a style of innovation development which can perfectly encompass the productive or scientific-technological ones and that can be extended to all sectors (Gómez de la Iglesia, 2021). It differs from other types of innovation both in its results (sustainable, responsible, distributed…) and in the relationships it generates, through new forms of cooperation and collaboration, as well as in the cultural values that drive it.

“The reflection that seemed most interesting to us was to find forms of collaboration or co-creation, in which the talent of the artists would not only be applied to cultural or artistic production, but could have a horizontal transfer of value to other sectors. This is why we are very interested in working with other sectors of the economy, of society, to generate projects in which an artist can contribute and add value from their expertise. Not because they learn to internationalise themselves, or because they learn to create a business plan, but because their knowledge has an impact that generates value in another sector. That is the idea, and that is what we are experimenting with.”

Clara Montero is the Cultural Director at Tabakalera International Centre for Contemporary Culture in San Sebastián, Spain and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 3rd of June 2021.

In this context, organisations are recognising the need to be “responsible”, learning together with other stakeholders, to increase their capacity to add value, in a broad sense of the term, to their social, economic or environmental surroundings both directly and indirectly (Berthoin Antal, Oppen, Sobczak, 2009). Innovation is applied creativity that generates value, it requires imagination, and imagination requires diverse stimuli, flexible environments and networks that can withstand it (Meusburger, 2009). Also professionals capable of relativising their knowledge and attitudes, citizens capable not only of tolerating what is different but also of encouraging it.

“By mobilising resources, by stimulating spin-off activities, by reinforcing the creative and innovative capacities of companies, culture helps to generate jobs, cultural and non-cultural, within companies, cultural or non-cultural. To clarify the debate, we could say that culture creates aesthetic values, activity values and development values, specific sources of employment that arise at each of these levels” (X. Greffe, 2001). It is necessary to recognise the innovative potential of the cultural and creative sectors, to transcend their capacity for economic diversification and also to value their intangible potential for the well-being of societies as a whole in terms of inclusiveness, welfare and transformation. Culture has often been treated as an evidence of social or economic development (the consequence) but it is also, and above all, a source of development (the cause) (Amendola, 2001), a way of introducing innovation in society through attitudes and values.

“I think one of the most impactful roles that artists, art and creative work have to play is in terms of increasing wellbeing of society, the ability to really engage with different perspectives and increase our openness to others. And in turn this, has an impact on the economy. The idea of actually engaging in conversation, in dialogue and collaboration that cuts across different areas of society is something that artists have unique tools to engage with and to initiate and steer in the future. This will be a big factor in terms of really creating a society that is healthier… And that will really impact economy in the biggest sense as well.”

Over the past years, creativity and innovation have been widely linked. More research is still needed on the most effective ways of facilitating crossovers between the cultural and creative sectors and industries and other sectors of the economy. Creativity is not the only central resource of the post-industrial creative economy, but the creative industries, in its broad sense, operate as an information and coordination system within which new forms of symbolic production and consumption are organised (Gómez de la Iglesia, 2020).

Although the artistic and cultural world is creative, it cannot be said that it is necessarily innovative. It is creative in its expressions, in its ways of doing and thinking, but at the same time it needs to qualify many of its creative and managerial processes, to interact and contrast with other social environments, to set itself new conceptual, relational and technological challenges… (introducing open innovation). And it can contribute to finding answers to the concerns of the economic and social world to give itself new meanings, a new ethic and a greater perspective of the positive social impact of its activity (being an agent of open innovation).

“There is an obvious absence with regards to what happens in artistic practices by other sectors and other political spheres. Culture is simply not present there, it is barely called upon. Now this sphere is beginning to open up to some extent, but it is still very difficult to get other sectors out of this somewhat preconceived concept that the arts are, above all, a matter of leisure or that they are strictly a matter of cultural product consumption.”

Tere Badia is the Secretary-General of Culture Action Europe, a European network of cultural networks, organisations, artists, activists, academics and policymakers. Tere Badia was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of April 2021.

The change in economic paradigms and innovation models means that the roles traditionally played by different institutions and agents have changed. Concepts such as authenticity, reflection, flexibility, critical thought, diversity, distributed leadership or creativity have been added to the list of desirable attributes of people and organisations. A report published by the World Economic Forum (2020) on the future of jobs states that “in-demand skills across jobs will change in the next five years. The top skills and skill groups which employers see as rising in prominence in the lead up to 2025 include groups such as critical thinking and analysis as well as problem-solving, and skills in self-management such as active learning, resilience, stress tolerance and flexibility.”

“Culture and art, on the whole, and the skills of artists could be used in resolving pretty much any problem in society. But the essential thing here is that working life skills are more and more focused on originality and boundary-breaking endeavours, so that the artistic approaches methods could in fact be useful in any field.”

It seems that the economic world is looking for what characterizes the cultural world, and in particular the arts: the ability to work with uncertainty and risk, the capacity for divergent thinking, resilience capacity, the ability to move on the peripheries, to develop a balance between the tangible and the intangible, to manage talent, to nurture relationships between the strength of individuals and group creation, the combination of creativity, knowledge and an attitude or charisma…: “combining knowledge and skills specific to cultural and creative sectors with those of other sectors helps generate innovative solutions, including in information and communication technology, tourism, manufacturing, services, and the public sector”(New European Agenda for Culture (European Commission, 2018, 4).

It is here that the role of higher education institutions plays a fundamental role, as they must explore ways to provide their students with a wide range of skills that will enable them to face a dynamic and changing economic and social future: “higher education teaching needs to equip students with a wide range of skills needed in innovative and changing knowledge societies and economies. In addition to subject-based know-what and know-how, this includes skills for thinking and creativity as well as social and behavioural skills. Mastering a wide range of skills will facilitate students becoming true lifelong learners, able to face and act upon the uncertainty of the future” (Hoidn, S & Kärkkäinen, K, 2014, 47).

“There is great demand and need for creative thinking in all sectors of society, whether we are talking about big corporations or boards of directors, primary or higher education or public services. Actually, art could have a lot to give to all these places and sectors precisely in the area of creative thinking and viewpoints or introducing new perspectives and ways of processing issues. In that respect, the task of art and artists is really to be present everywhere. I think that in the future, as multiple skills and creative thinking will be emphasised, this will require that artists will more and more step outside their bubble and share their expertise and artistry.”

The relationship between arts, culture, creativity and research, development and innovation (R&D), it’s difficult to define in all its dimensions. Schemes usually pressed by science or technology, are not always valid and applicable to the creative and cultural sector, but it is necessary to understand arts and culture as a field of knowledge equal and complementary to others (Gómez de la Iglesia, 2021).

We can speak of research, development and innovation “in” the artistic and cultural sector, that carried out within the sector itself and its agents, and “on” the sector, that carried out both from outside and from within, where the object of study is the sector itself. Linked to the above, research “for” the arts can be incorporated, related to the existence of a vision that the arts, culture and creativity are not considered a first level field of knowledge generation for innovation, requiring other external ones connected to scientific or technological knowledge.

But the real challenge is to commit research, development and innovation processes “from” the arts, considering them as drivers of innovation in other fields playing a highly relevant and vehicular role, for example, in social or civic transformation processes. And also “with” the arts, where object and subject are combined in both fields: “promoting that exploratory capacity to work on the limits, on the peripheries so characteristic of the art world, and to apply it to other contexts; to be able to raise new questions in the search for new answers”. (Gómez de la Iglesia, 2021, 81). At this point, is where cross-fertilisation, transdisciplinarity or hybridisation processes come into play.

“Artists spend many years speculating and working on empty canvases, on blank pieces of paper. I think that the ability to face complex situations, of which there are no preconceived patterns, is one of the fundamental roles that all those who are trained in artistic practices and methodologies can have. So is the capability to be critical and to question everything. We are very used to take, both socially and politically, many things for granted and we are unable to question many other things parting from these spheres. And in this respect, the arts operate with much more freedom and are much riskier when posing challenges, generating critical awareness about how we situate ourselves in our relationship with the world and with the rest of humanity and the environment, or even when suggesting where the cracks and the problems of the current system are, whether the system be economic, social or any other type.”

Tere Badia is the Secretary-General of Culture Action Europe, a European network of cultural networks, organisations, artists, activists, academics and policymakers. Tere Badia was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of April 2021.

“In the context of design, Don Norman talked about the need of translators between practice and theory. This is necessary and also possible. For interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary work to happen, we have to teach or have a curriculum of translators in the wider sense. The in-betweeners is a really good word for that.”

Eik Hermann is a philosopher, working in Estonian Art Academy as a lecturer of philosophy and research consultant for the Architecture Faculty. Erik Hermann was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 6th of May 2021.

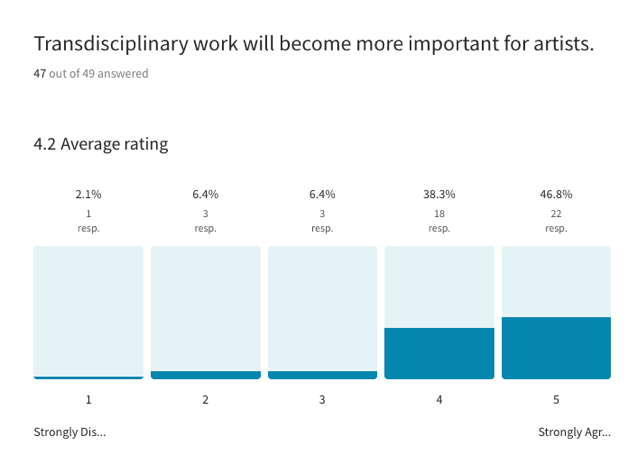

The 85% of the interviewees in FAST45 project state, that transdisciplinary work and practice will become more important for artists:

In recent years, very interesting initiatives (see below at chapter “some cases”) have emerged that address different types of relationships that promote co-research and co-creation with and from the arts and culture, fostering transdisciplinarity in research and innovation processes. People from the arts and the organisational world seek to learn from each other and create new knowledge together in a shared value system.

These new relationships are the subject of study both by academics, artists and artistic and cultural organisations themselves, who seek to better understand processes and outcomes. Ultimately, many studies and opinions indicate that working with the arts can catalyse the creative capacities of the organisation and promote productive processes of innovation. On a social level, it can promote cultural democratisation and improve people’s self-esteem.

Also, among these interviewees the:

Despite this, it should be taken into account that international reference standards for measuring innovation, research and development in European industrial organisations, such as the Oslo Manual, the European Innovation Index or the Frascati Manual, provide a set of indicators difficult to apply to the cultural and creative world as well as the lack of indicators linked to the impact of creativity on innovation processes in other sectors.

“I believe that artists are one of the professions whose life choice is most dedicated to a process of research and knowledge. There are few professions that involve so much dedication to a process of constant and personal research. And, therefore, this means that they generate knowledge that cannot be generated from other specialised or academic fields; and they also have the capacity to include the component of disruption, or to propose future scenarios that we will probably not be able to reach from other classical fields of knowledge.”

Clara Montero is the Cultural Director at Tabakalera International Centre for Contemporary Culture in San Sebastián, Spain and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 3rd of June 2021.

Klick to read the full report about “The role of public policies in developing entrepreneurial and innovation potential of the cultural and creative sectors” (European Commission, 2018).

Read deeper into “Artistic interventions in organisations: finding evidence of values-added” (Berthoin, A & Straub, A., 2013).

“Can an artist contribute in making professionals in another sector, or a company, more innovative, more competitive? Well, probably, yes, and it’s interesting to explore that area.”

Clara Montero is the Cultural Director at Tabakalera International Centre for Contemporary Culture and was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 3rd of June 2021.

Four main models can be established for the relationship between the arts, culture and creativity and companies, whatever their sector:

Those based on support programs for cultural organisations or initiatives, more closely linked to patronage or sponsorship.

Those linked to the use of arts and culture as instruments for the design of the offer or service, marketing or corporate communication.

Those linked to the use of arts and culture as elements of internal sensitization, training or support for team building.

Those based on artistic intervention programs in organisations for strategic reflection for organisational transformation, change and innovation in products, services and/or markets, or corporate social responsibility for social innovation.

The following are some examples in the industrial field:

Re-FREAM, a pillar of S+T+ARTS programme, was a collaborative research project where artists and designers teamed up with a community of scientists to rethink the manufacturing process of the fashion industry. The goal was to co-research and co-create new concepts for the future of fashion by means of new processes and aesthetics that are inclusive and sustainable by using 3D printing, electronics and textile or eco-innovative finishing in order to create a new value chain for the fashion industry.

“The key is that the people who have done creative work need also to interact with other disciplines that in the current paradigm are not necessarily considered to be creative. Having this kind of experimental, a testing mindset, and the ability to make “bread out of shit” as the old saying goes, in a very complex situation – this is the key skill in terms of navigating in this ever changing complexity.”

Marten Kaevats is an architect, urban planner, and community activist, at the time of the interview he worked as Estonia’s National Digital Advisor. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Marten Kaevats on the 7th of May 2021.

Siliconas Silam, a company dedicated to transforming silicone into products for industrial use, worked together with artist and educator Paola Guimerans in the search of new orientations and business developments, on the basis of the company’s own talent, experience and knowledge. An Open Lab, facilitated by Conexiones improbables, in which they also collaborated with makers and which resulted in the Think-of-Silicone project, a new line of research to manufacture silicon suitable for 3D printing.

“Art can carry a lot of information and emotions. This is extremely important for society, because it is a cultural treasure and at the same time forms the basis for learning how these mechanisms work. It’s also the basis for companies to learn how to use emotions and information in a commercial way. Art has paved the way on many levels, because in a commercial context people have no room to experiment. Art is an open chaotic workspace without fixed rules, with constantly changing techniques that allow new forms of expression through which people can express, interact and learn without corporate influence.”

Sven Bliedung is the managing director of Volucap the Studio for volumetric productions He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 22nd of April.

Better Factory is a European project funded by Horizon 2020 and driven by a consortium of 28 partners from 18 European countries. The initiative brings together key actors in the fields of technology, arts and innovation providing a framework to manufacturing SMEs for the development of new and personalised products and the creation of innovative services around them. An initiative that aims to help European Manufacturers to be more competitive in a global market through collaboration.

“I think artists must begin to see themselves more and more in different roles and places. It is a radical change that probably. Feels so big that it can be difficult for many to find out that the world they should be working in is not the same as they had assumed. Roles must be extended and here is where educational institutions are at the forefront of development, because it is education that ultimately gives artists the tools to think and to see themselves putting their talent to use in different place.”

Check out the FAST45 art school futures scenarios!

TELL ME MOREDive into the research

Discussion

No feedback has been added yet

Share a Thought