Institutes of Higher Arts Education have a rather conservative image due to their lack of diversity both in the audiences concerned and in the practices embraced, but also in the courses offered, with a rather narrow vision of the profession of artist. Faced with the profound changes in societies – equity, inclusion, new needs of the profession, ecological issues, digital development, etc. – the IHAEs should engage in the necessary transformations for which they need to reconsider their missions and rethink their processes. Through current examples but also through future scenarios, this narrative aims to draw the future type of IHAE we need in 2045.

Written by

Samuel Chagnard,

Sandrine Desmurs,

Jacques Moreau and

Nicolas Sidoroff

Cefedem Auvergne Rhône-Alpes,

2022.

According to our interviewees panel but also according to some authors, IHAE have a rather conservative image due to their lack of diversity both in the audiences involved and in the practices embraced, but also in the curriculum offered, with a fairly narrow vision of the artist’s profession.

“Things become more segregated, separated. The arts have hierarchical structures and are elitist and have very little to do with connecting with society and community, and become more and more institutionalised and privileged, elitist.”

This vision of IHAE, considered as conservative and disconnected from society (based on the idea of academism, notion of excellence) is not new.

“All the articles shed light, directly or indirectly, on the strength of the rhetoric of ‘talent’ in the art world and its specific role in masking, obscuring and rendering invisible the social mechanisms of the construction of inequalities at work in its schools.”

“We need to be updated and have decolonised perspectives in the curriculum. What men are we talking about when we talk about the impact of men on the planet? Maybe it’s not the same for everyone.”

“The artistic life has been based on how it goes back to how things have always been done and what it’s based on what you know, rather than what you don’t know. In our institutions and our sector, a lot of it is based on what you know. And that’s what people from the outside feel, well: ‘that’s not for me because clearly I don’t know what you know, and you don’t want to know about what I know and what I could bring to this organisation or this work.'”

Sean Gregory is Vice-Principal and Director of Innovation and Engagement, for the Barbican and the Guildhall School in the UK. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Sean Gregory on the 23d of April 2021.

As Marie Buscatto pointed out, the lack of diversity in IHAE, on the teaching staff as well as on the student and stakeholder side has a huge impact on the professional arts world:

“Analysing the feminisation of the world of visual arts, Dominique Pasquier considers that ‘the opening of all art schools to all artists without distinction of sex can be considered a decisive step for women artists’ (Pasquier, 1983, p. 425). If it is not enough to ensure the complete feminisation of this world and equality of conditions, it favours a decisive entry of women into the professional world of visual arts.”

“I think perhaps sometimes we are looking in too narrow boxes at the ways in which artists are trained and the kinds of skills that they are focusing on during their education.

…

I also see […] a tendency to want to box things up and keep things as of always been so sort of to protect the ways in which certain areas of the arts have been managed and approached, you know, over time, sort of trying to keep hold of the old ways […].”

“I’m sorry to say that, but higher education and our academic world is very categorized and structured and not interdisciplinary at all.”

Horst Hörtner is the director of the ars electronica Futurelab, a department within the context of the ars electronica in Linz (Austria). He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 11th of May 2021.

“The thing that we are teaching is not so outdated, but maybe the way we teach them is becoming outdated. Maybe it is part of the situation that we are still assuming that when you are a good practitioner, then you’re also a good teacher. And this is not the case at all.”

Eik Hermann is a philosopher, working in Estonian Art Academy as a lecturer of philosophy and research consultant for the Architecture Faculty. Erik Hermann was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 6th of May 2021.

The aim of Institutes of Higher Arts Education is to guarantee (through coordination, systematisation, and organisation of actual and potential behaviours) and delimite the “whatness of what is” (Boltanski 2011). Indeed, the institutions are grappling with the need to broaden their curriculum but often fail to emerge from the juxtaposition of new disciplines (without transversality or globality and comprehensiveness).

“My two reports have explored the functioning and dysfunctions which result from the respect of the said conventions. I have shown how the world of the arts, organised into disciplines, is governed by rules, codes, standards, conventions whose sustainability is guaranteed by their teaching in conservatories. […] How indeed can one qualify as creation, that is to say entirely new, an object steeped in constraints born out of respect for standards to which the ‘creator’ conforms?”

Reine Prat, is a French senior civil servant, honorary inspector general for creation, artistic education and cultural action at the Ministry of Culture. She is the author of two ministerial reports, in 2006 and 2009, for gender equality in the arts and culture sector in France. Prat is here cited from her book “Exploser le plafond – Précis de féminisme à l’usage de la Culture” (2021).

Digital technology has made its way into the art world, first as a technical support for the production of works, until it has become a medium in its own right. Artistic creation and its representations are influenced, adapted, modified by emerging techniques. These transformations shake up artistic imaginations and call for new skills, new knowledge and new literacy.

“We are still at a phase where a lot of schools are sticking to a kind of traditional model and not necessarily addressing technology in the way that I maybe intended, which mean not just as a tool, but more as a medium and as a subject of research and discussion and critical discourse.”

Twenty years ago, UNESCO published a universal declaration on cultural diversity:

“Identity, diversity and pluralism

Article 1 – Cultural diversity: the common heritage of humanity

Culture takes diverse forms across time and space. This diversity is embodied in the uniqueness and plurality of the identities of the groups and societies making up humankind. As a source of exchange, innovation and creativity, cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature. In this sense, it is the common heritage of humanity and should be recognized and affirmed for the benefit of present and future generations.”

Already, on October 7, 2000, during its general assembly, ELIA and its members signed a manifesto to engage higher artistic education in the necessary changes to come:

“Academic systems need to become more flexible”

“Higher arts education institutions should be laboratories and not museums”

“It is necessary to engage with other cultures to ensure that knowledge of their artistic achievements is not suppressed or removed from the dominant version of European art history.”

ELIA Manifesto, 2000

20 years later, this undertaking are still intact. And the 2010s were marked by many social protest movements within the worlds of culture.

These last years have been marked by strong social demands for more equity, diversity and inclusion in society. The Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements, for example, have had an international impact. And the worlds of the arts have not been spared, on the contrary, because these fields of activity are all as borrowed from discrimination of all kinds and relationships of power and domination leading to multiple forms of violence.

Numerous initiatives in the artistic and cultural fields have emerged in recent years to address these issues and develop concrete courses of action.

Let’s take the example of the SHIFT project (for Shared Initiatives For training). For two years, 9 European cultural partners (networks and European cultural platforms) have joined forces to work on the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (for the common project of peace and prosperity) by focusing on 3 that are climate change, reducing inequalities and gender equality.

The partners produced online resources on the following themes

including:

Gender and power

Example of work on gender and power: analysis of the #MeToo movement in culture:

Since 2017, the project has focused first on understanding and approaching such a topic in the world of culture, then analyzed examples of situations of sexual harassment and abuse of power and then finally, set about proposing courses of action to create an equitable and safe professional environment for professionals in the field.

=> RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EUROPEAN CULTURAL NETWORKS

1) Put time and effort into formulating and building consensus around precise terminology.

2) Work towards creating a sector-wide standard for arts leaders to receive formal training in creating safe professional environments.

3) Understand how precarious working conditions increase vulnerability to potential abuse. And take action!

4) Prioritise long-term, structural work on gender equity and diversity within your sector.

5) Set aside a dedicated budget for training and for specialists.

6) The support of European cultural networks is needed to foster structural change on the transnational level.

Working on diversity and inclusion

Example of work on diversity and inclusion issue: extract from the Diversity and Inclusion Report:

SOME KEY CONCEPTS FOR THE CULTURAL SECTOR

Here we examine some of the history of the themes of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging, specifically:

The art sector is not naturally a zone of moral improvement!

An example of this was recently demonstrated in the context of classical music, where black scholars confronted white supremacy as was reported by the New York Times. Journalist and music critic Alex Ross (2020) outlines “The field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also giving new weight to Black composers, musicians, and listeners.”

Ross further points to a problem on a general scale:

“The ultimate mistake is to look to music—or to any art form—as a zone of moral improvement, a refuge of sweetness and light. Attempts to cleanse the canon of disreputable figures end up replicating the great-man theory in a negative register, with arch-villains taking the place of geniuses. Because all art is the product of our grandiose, predatory species, it reveals the worst in our natures as well as the best. Like every beautiful thing we have created, music can become a weapon of division and destruction. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, in a characteristically pitiless mood, wrote, ‘Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.’”

Art school research projects on diversity

For other examples of research conducted on these themes, see also

These movements of societal claims resonate with demands within our institutions for:

1. Taking into account the plurality of artistic practices (which are always in movement) and the variety of professions

“What we have to look for is not that each student does the same as the previous one, and neither for them to be evaluated according to what he or she has done comparatively, but to find the way in which students’ talents can emerge. This is a system that is based on trust on them, and it is also based on the fact that this trust understands the students’ circumstances and concerns. For me, the teacher has become a facilitator of personal paths. Not a limiter of existing paths.”

Jaime de Los Ríos is an artist, curator and specialist in new media and new technologies currently based in Spain. He was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 21st of May 2021.

“We are frequently thinking about how to change and modify processes of knowledge transfer or shared knowledge creation, because we believe that it is crucial to start out from situated knowledge that is perhaps not as methodical or not as articulate as it may be in the Academia, but which is remarkably valid to integrate. Not to belittle the work done at these institutions, which I think is very important, but to open up the spans of knowledge to other kinds of practices that are much more hands-on, more collaborative and somewhat more ‘illegitimate’.”

Tere Badia is the Secretary-General of Culture Action Europe, a European network of cultural networks, organisations, artists, activists, academics and policymakers. Tere Badia was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 7th of April 2021.

This plurality refers once again to the question of diversity and inclusion in order to welcome and legitimise all practices and cultures.

French example of Fondation Culture et Diversité, programs for access to major cultural schools.

French example: CineFabrique, a national public film and audiovisual school with a project of real diversity (social, cultural and geographical) and equity with, among other things, an alternative recruitment process allowing access to studies for a wide variety of people with very varied initial studies (only a high school diploma is required), but also offering 5 courses of study in order to open up the field of possibilities and to promote the entirety of a plural field of study and the related professions.

2. Hearing the voices of students and stakeholders. The governance body needs to deal with the student voice

“A further transformative trend has been the strengthening of student voice both within higher education generally and specifically in HME (European Association of Conservatoires, 2017; Coutts, 2018). As clear inheritors of the future of the professional music industries, and often arriving in HME with significant prior achievement and experience, students as partners have a critical role for HME in adapting to contemporary contexts, including for example in making a turn toward engaging with societal change and diverse communities.”

Let’s have a look at the young European Performing Arts Students’ Association (EPASA) created in November 2021 and their Belief:

“Our Belief

We believe that, in order to be successful, a performing arts institution must encourage a healthy partnership between administration, staff and students. An institution that provides an inclusive and accessible platform that empowers the student voice not only creates passionate and advanced artists, but also conscientious, valuable members of society.

We equally believe that students have the purity of thought and can therefore be the best defenders of the humanistic values within music and arts education. Accordingly, a well-supported Student Representation System (SRS) has the freedom to advocate for an arts and music education unrestrained by any political and financial control.

We strongly believe that in any Higher Music Education Institution, region or country, beyond unfavourable specific (financial, political, structural) circumstances, a good and effective SRS can be settled without too much financial or infrastructural effort. It is predominantly about changing the institution’s mind-set as a whole, taking the action, and ensuring some minimum requirements are met in order to provide a platform for the student voice to be heard.”

What do the art accreditation agencies say about governance?

EQ Arts

1.5 The institution has an appropriate organisational structure, allied to clear and effective decision-making processes that enable it to realise its mission and meet its stated strategic objectives.

2.2 Study programmes, and their intended Learning Outcomes (LOs) are designed, and regularly approved with the involvement of internal and external stakeholders.

6.1 The institution’s internal communication systems are accessible to all students and staff and enable vertical and horizontal interaction between all its internal stakeholders.

EQ-Arts Standards and Criteria

http://www.eq-arts.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2021-Final-SER-Template-endorsed.docx

Mimi Harmer, AEC Student Working Group Co-Chair, presentation at MusiQuE 2nd webinar « Involving students in QA », november 29th, 2021 (from minute 28’05 to 42’34)

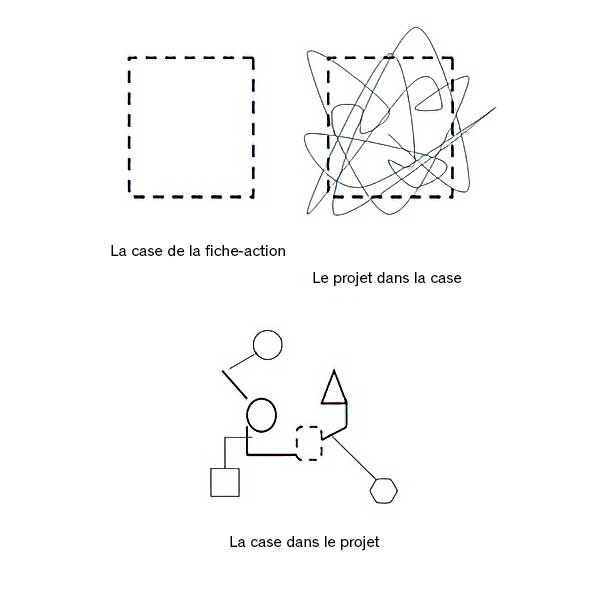

3. Creating bridges between disciplines within and between people to build transdisciplinarity in our curriculum. Some of our students arriving in our institutions refuse to fit into boxes we build for them.

“As of now, we are very vertically organized. This organizational structure doesn’t only hold for study programs, but also for our general organization, for our administrations, and the organization of our technical environment. We must think more horizontally, more connected, more as a whole. We need to think in processes, collaborations, and interdisciplinary terms. I see daily, how important this topic is.”

Susanne Stürmer is the president of Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, Germany. She was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 14th of April 2021.

“Thinking about our audiences, our participants, our artists, our programming, our curriculum, in a very different way. […] We need as leaders to trust that process, and not feel we have to be the experts and know everything ourselves. It’s our role as much to facilitate and to use our knowledge expertise, to have more, to help other ideas, to grow and develop and take form.”

Sean Gregory is Vice-Principal and Director of Innovation and Engagement, for the Barbican and the Guildhall School in the UK. The FAST45 Knowledge Alliance interviewed Sean Gregory on the 23d of April 2021.

For example, here is an extract of the items for Self-evaluation report requested by Enhancing Quality in the Arts Agency for Institutional/Programme review:

“1. Quality Assurance Policy

1.2 The institution’s mission, strategic plan and policies respond to, and impact upon, the Creative, Performing Arts and Design (CPAD) sector and societal needs locally, nationally and internationally

1.4 The institution has an Equal Opportunities policy that is applied to all its operational activities

2. Student-Centred Learning

2.5 In addition to specific artistic competences, the intended LOs include transversal and interdisciplinary, intercultural and international competences.

4. Human Resources

4.3 The institution recruits the teaching, research, academic management and study support staff in accordance with their equal opportunities policy that takes account of the needs of diversity.”

An example of an illustration of how to get out of the box

The technologies of the digital world shape today our relationship to the world and are the vehicle of economic, social and political ideas (authors speak of digital culture(s) as Milad Doueihi, 2011). The meeting of the triptych arts-sciences-technologies allows to make new imaginary, through:

By evoking the ecosystem of the digital arts, Clément Thibault (2021, 46-49) speaks about change of paradigm (in the sense of Nathalie Heinich applied to the worlds of the arts): “a new paradigm modifies the way of thinking the art, of conceiving it, of showing it, of distributing it but also the way of living of it when one is an artist.”

We note the interpenetration of digital uses in all the artistic forms of today (visual arts of course but also live arts, fine arts,…), which refers to the protean character of digital arts and the transversality of these practices.

“Writing software is creating a world with its own logic, laws and aesthetics.”

Rocio Berenguer is a playwright, choreographer and transdisciplinary artist.

Computer code and software production convey representations of the world that must be studied and criticised because nothing ensures that they do not build the same problems of exclusion, manipulation and power.

For example, in the musical world, digital audio stations are mostly designed by default to make music in equal temperament, which is a reflection of the dominant White musical culture of Central Europe.

“If a musician opens a new composition and they are given a 4/4 beat and equal tempered tuning by default, it is implied that other musical systems do not exist, or at least that they are of less value.”

The artistic performances are transformed as well in their format as in their relation to time and space. And the health crisis with the successive confinements have reinforced this phenomenon of “platformization” of the Culture (Verges 2021) with this new digital marketing which invades the cultural places. The digital is also a channel of transmission in front of the link which is transformed between the traditional places of the culture and the public (with the idea that the spectacle goes towards the public and not the reverse as before).

“Any teacher that can be replaced by a machine should be!”

But what about the impact of digital technology on transmission/mediation practices? What about the relationship between pedagogy, science and technology, especially in the artistic field?

Artificial intelligence is present in all future scenarios, and in all areas of society, including learning and teaching. Today, research in this field is attracting all eyes. However, it is quite complex to build a measured knowledge of the subject in the face of often fantasised discourses. Understanding what AI is, where we are and where the research is going are essential points on which to build.

For example, through the process of deep learning, artificial intelligence systems consume available data. Yet these intelligences “can only see the world as a repetition of the past. This has deep ethical implications” (Tuomi 2018, 4). In the world of learning and teaching, it is therefore interesting to study the transformations at work in the emerging knowledge society.

“As a result, there is a risk that AI might be used to scale up bad pedagogical practices. If AI is the new electricity, it will have a broad impact in society, economy, and education, but it needs to be treated with care.”

“The history of Artificial Intelligence append to us that the trajectory of technological innovations is never straight […] To all those who announce that an autonomous intelligence will be among us in 2025, such as the transhumanists, proponents of Ray Kurzweil’s Singularity theory, we must remember that the science being done follows a much more original and subtle path than a simple straight lin.”

From the FAST45 project about the futures of learning and technology

These changes are now driving educational communities and call for research, debate, knowledge building and critical thinking.

For example, Pascal Plantard (2013), an anthropologist of the educational uses of digital technology, proposes to reuse the work of Lucien Sfez (1992) who described 3 visions of the world in terms of the relationship with technology:

with technique: Man uses technique as a tool to act on the world: “Man uses technique, but does not enslave himself to it” (Plantard 2013, 8).

in the technique: The technique is considered as an environment and the subject is placed in this environment to which he must adapt. “Man is ‘thrown into the technical world’ which becomes his nature” (Plantard 2013, 8).

by the technique: Sfez (1992) speaks here of Tautism (contraction of tautology and autism) “By the technique, the man can exist, but not out of the mirror that it tends him.” (Plantard 2013, 8)

Three relationships to technology that are side by side and intertwined today. Therefore, in the digital age, Pascal Plantard proposes to the educational community to build its training systems “with digital technology, in digital technology and through digital technology” by adding the adverb TOGETHER. Clearly, he invites to build skills (with), to know how to adapt (in) and to experiment (by) to be an actor of the transformations at work.

The teaching of the arts is prey to the same questions as to the future of technological practices in the service of learning and teaching.

“Art has a fundamental place in our lives and in our societies on the question of the awakening, of the enlightenment, to carry the glance somewhere, to assume the completely subjective part taken by an artist on a way of seeing and of looking at the world. […]The art education institutes should contribute to teach on the forms that art takes. Instead of teaching the dogma by saying how art should be, trying to understand what the artist wanted to tell by making art using digital tools, artificial intelligence, etc.”

Emmanuel Verges is a cultural engineer, co-director of the observatory of cultural policies and director of the Office. Verges was interviewed by the FAST45 Knowledge Alliance on the 28th of April 2021.

These trends invite us to move from an institution that passes on (heritage, repertoire notion, excellence reduced to the canons of perfection, of know-how) to an institution that enables (whose primary role is to give birth, to allow emerging, to allow the artist-student to gradually create his/her own definition of benchmark of excellence, in partnership with the institution and from which the institution will assume its role of evaluator).

The project must allow both:

From Bachelor 1, students are considered as:

The project is built and carried out in different stages, each of which is presented, discussed and evaluated:

Teaching is not organised in a curriculum of knowledge to be acquired.

But in terms of resources for student-led projects,

At each stage of the project:

In relation to the project, its role is to:

In relation to the place of education, its role is to:

The contract is like a “research contract”, which determines:

The institution is a “partner” of the student in the realisation of this project. As a partner, it must continuously:

It is the student’s responsibility to:

The Learning Planet Institute has developed a Frontier of Life Sciences Bachelor’s degree (created in 2011) which implements:

https://hal-hceres.archives-ouvertes.fr/hceres-02027446/document

https://learningplanetinstitute.org/en/education

The training is delivered for a large part in the form of interdisciplinary experimental projects: centered on an open question, the production and use of new data, they must be an opportunity to explore and not only to reproduce expected results. Integrated into research projects from their first year, with help of researchers, students have to:

About the Learning Planet Institute

As written on the web site of the learning planet institute :

Molecular painting laboratory (Bachelor 1) (within the training in 2014)

In the 1st year, students had to define the main concepts of molecular painting by formulating hypotheses to solve the problems they encountered. At the end of a bibliographic work, they presented their results which were evaluated by the 2nd year students. During this time, they participated in the research work carried out by the 2nd year students and under their direction. At the end of this work, the 2nd year students analysed their own work and presented the results to the L1 students who evaluated them. Finally, the 1st year students then proposed projects that they would have to carry out the following year. The selected projects were submitted for opinion to 2nd year students. The 1st year students then wrote their project in the form of a research proposal.

Engineering Project (Bachelor 2)

Students prototype ways to observe and/or protect biodiversity. Through a literature review and a questioning of the possibilities and limitations of DIY methods, they design, build, test prototypes for participatory research. The cohort of 40 students join and contribute to a scientific movement of citizens of the sea, yachtsmen, fishermen, islanders… who want to contribute to the observation and preservation of biodiversity throughout the world, in fruitful interaction with researchers, politicians, associations and companies.

Nanomedicine Projects (Bachelor 2)

This collaborative course proposes the students to achieve experiments to answer scientific questions: which is the more relevant formulation of an antibiotic able to kill yeasts at low concentration and to have low toxicity against mammalian cells? Are there any physico-chemical characteristics able to explain the results?

All students will be required to work in collaboration with 3 other students in a group. Each group has to prepare, characterise and evaluate the antifungal activity and the toxicity of one formulation.

CRI Fellows Project (Bachelor 2)

CRI [Centre de recherches interdisciplinaires, Center for Interdisciplinary Research] research and “Licence Frontières du Vivant (LFDV)” (Frontiers in Life Sciences Bachelor’s degree) are teaming up to co-create a research course for 2nd year (Bachelor 2) students called SCORE: Student COllaborative REsearch. This is an exciting opportunity to connect education and research at CRI in a meaningful way, involve students in research and open the projects to a broader audience.

Reproductibility Project – (Bachelor 2)

This course aims to develop reflexivity about how data are produced, analysed, shared, stored, in a research project. Students work in groups of 3-4, on a dataset proposed by researchers. The course focuses on reliability and reproducibility issues currently faced by the scientific community, analysing underlying practices, guiding the students to develop reliable research practices.

“Life Sciences for SDGs” Project – (Bachelor 3)

During this semester, students will have to address concrete issues, in connection with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which will be proposed by professional-mentors from the socio-economic or associative world. Put in the position of apprentice researchers, the students will work as a team to design a sustainable and eco-compatible solution in the form of an interdisciplinary scientific research project.

(In September 2022, the Learning Planet Institute starts a Bachelor Degree focused on SDGs called “Bachelor ACT ”)

Based on the experience set up at Cefedem Auvergne Rhône-Alpes since 2000, on the reflections of Jacques Rancière in Le maître ignorant (first edition in 1987), itself based on Joseph Jacotot (1770-1840).

Project-based and contract-based training implies significant structural changes. For artistic practices, the projects can be very diverse and the institution must be able to accommodate them in all their singularities. They require human resources that are quite different from one project to another, including possibly human resources not present in the institution. One possible response is a support system in the form of “resource hours” made available to the student for the realisation of their project.

This system is based on the notion of “resource persons” (any person who can help the student in her or his project). It distinguishes and specifies those who are asked to do specific and additional work requiring a work contract with the institution (in that case, resource persons paid by this system of resource hours).

With the support of a referent-teacher and the administrative team, each student thus has a financial volume represented in the form of hours to benefit from assistance outside the institution.

Such a system requires an organisation

Each student must determine their project with a list of “resource persons” to be solicited to accompany the project (specifying the learning objectives of such work), and a choice of distribution of resource hours on one or more particular aspects when necessary.

The referent-teacher validates this project in partnership with the student and confirms the choice of the resource person(s) to be solicited. Then, the teacher works mainly as an “Ignorant Schoolmaster”, enforcing the framework of the project set by the institution and helping the student to clarify her or his questions, research and learning.

After confirming the project, the student is responsible for contacting the resource person and making sure that all administrative procedures are completed.

The administration is then at the service of each student lead after the project is contracted.

An example of a “resource hours” system

An example of a “resource hours” system

Such a system has been in place since 2000 at Cefedem Rhône-Alpes, now Cefedem Auvergne Rhône-Alpes. This center is based in Lyon, France, under the authority of the Ministry of Culture, and offers two-year programs leading to the Music Teacher State Diploma, geared towards the teaching of music in conservatories and all music schools established throughout the country. In 2003, France had “more than 3,300 public schools (run by public authorities or by associations subsidised by these authorities)” (Ministère de la culture et de la communication 2004, 5).

This “resource hour” system was one of the elements that made it possible to welcome all the students, whatever their practices. From the beginning, the center has chosen to have a permanent team, therefore necessarily reduced but allowing a collective follow-up of the students. So, all the knowledge and competences cannot be present within the structure, while this team wish to accompany all the practices of the students. They have several long devices to carry out, each one with a specification: for example, those of performance projects (Charles, Scheppens, Hahn, and Clément 2006), or research-action (Chagnard, Haranger-Segui, and Sidoroff 2017) or practice-inquiry (Desmurs, and Sidoroff 2018). Each time, such a project is negotiated between the student and the referent-teacher. The latter ensures that the project remains within the framework set by the institution, i.e. that the student can go through the essential issues associated to each device. In defining what the student wishes to do, he or she must identify the resources to be mobilised, both material (books, articles, videos or anything else, but also including the necessary equipment) and human (“people who have skills and knowledge relevant to” the student’s topic, University of Maryland 2020). The latter bring together all the specialists in the different aspects of the question worked on by the student, allowing her or him to bring them together and immerse them in their contexts and ways of doing things. The Cefedem team also feeds this list of people. Very often, it is necessary to “invent” such people by making their typical profile. With the networks of the student, her or his colleagues and those of the Center, augmented by some internet research, one can regularly find almost this profile, or two persons responding to the very most of the expectations. The definition of the project resources is not just a list, but for each one, the student has to specify what he or she wants and plans to find in/with it. For many of the people listed, an interview or a discussion in connection with an observation in a professional context (where the resource person is already paid) is sufficient. But, with some others, it may be interesting to plan a specific job, requiring remuneration and an employment contract as a trainer for the student. This is where the “resource hours” budget comes in.

The specifications of the action-research program describe it as follows:

“Each student has a budget of 6 hours of resources to pay for outside contributors (called ‘resource persons’) for specific requests necessary for the development of the program: interviews with a professional, work with a researcher, participation in training courses, professional seminars, etc.

Some of these hours may be shared with other students.”

(FDCE 2021, 2).

The Cefedem chooses not to make employment contracts of less than 3 hours, to guarantee that there’ll be enough time for the student to have a minimal professional exchange (and to limit the number of contracts to establish).

It is not easy for students to understand how it works, nor for the resource persons solicited. Several editions of the document « Les personnes ressources, comment ça marche ? » (“The resource persons and resource hours, how does it work?”) were necessary. This document details the conditions and rate, so that the student can contact the resource person(s) and explain how it works. This document specifies also that these contracts can be of different types according to the status of the person to be paid, and that this budget of hours can also be used to pay or participate in the pedagogical costs of an enrolment for a training course, a teaching, a seminar, etc. The teacher also specify that “it is possible—and even advisable—to pool resources between several students with similar projects and needs” (FIN 2020, 4), so that the students exchange among themselves on their project and research to see if it could be interesting to meet and work together with the same person, not necessarily for the whole time. For example, two students wishing to discover jazz could share a time on cultural inputs and resources, and each one also takes a more personal time on the specific jazz practice she or he wishes to work on. After agreement with the referent-teacher, the students fill in a form so that the administrative team of Cefedem can contact the designated persons and establish employment contracts. Then, the student is responsible for the return of the attendance sheet signed by the persons in question.

On the students’ side: on the one hand, the work on the notion of resources through the contract requires them to explain the resources they already have, those they know are available, those that are possible, those that can be envisaged and those to be found. This set of resources is often far too large for the time available in the training! That is to say that they have to choose with the referent-teacher the ones they prefer. This is one of the ways to specify and refine the project. And after, they can, outside the institution, continue their research, having already some trails (this is also one of the questions in the assessment interviews when the device is done). On the other hand, they are in a position of responsibility towards the people they are asked to work with and towards Cefedem. The time allotted is not very long: it is not a question of taking a weekly course over the two years, but of choosing to work on this and not that, thus putting oneself in the position of an active learner on this learning, and still refining one’s project. The fact that there is an employment contract helps to position oneself in this way. The fact that there is a remuneration allows some students to contact and work with people they would never have imagined or dared to ask.

On the teacher’s side, finding oneself accompanying a project on a musical practice that one does not master is very rich in learning. (I’m a specialist of the techno-electro musical underground practices, and you want to work on the influence between Mozart and Haydn on their String Quartets?) The referent-teacher is then a specialist in learning, especially in this learning device and in its training issues. He or she is not a specialist in the content, others can take charge of that if necessary. And this position of “Ignorant Schoolmaster” as developed by Jacques Rancière (based on the experiences and writings of Joseph Jacotot), is very formative, and transferable with contents in which the teacher is a specialist. To allow the students’ intelligence to function with others, without explaining: to emancipate.

“His mastery [Jacotot’s] lay in the command that had enclosed the students in a closed circle from which they alone could break out. By leaving his intelligence out of the picture, he had allowed their intelligence to grapple with that of the book [Télémaque by Fenelon, in French with a Flemish translation, delivered to the Flemish students to learn the French, alone]”.

(Rancière 1991, 13).

On the administrative side, each year, 90 students work with about 200 different resource persons paid with this system, from 3h to 14h. The follow-up is a large time job, because of the number of both the students, all autonomous, and the resource persons with very different status depending on their situation at the time. This follow-up begins with having in time the right informations needed to make the employment contract, ends with making the payment, and in the middle, all little but numerous negociations with students, trainers and resource persons.

This system needs the people in the institution to cooperate with each other: the students, the teachers and the administrative staff have to work together to make it work.

This proposition for “opening up” the institutions is based on the experiences of:

Considering that some artistic practices do not yet have instituted degrees, or not enough;

Considering that an entry “level” based solely on a school diploma creates social selection;

Considering that a questioning based on an experience, and/or a desire for research located in a professional exercise is an excellent motivator to follow a higher education…

Provide study conditions adapted to the living conditions of the students received. For example in terms of temporality (with the possibility of evening classes, weekends, holidays, etc.), the presence of young children (a crèche and a kindergarten included in the institution), catering (solidarity canteen and shared, natural market not far from the institution, etc.).

Take into account the different statuses of students (initial training, employee under employment, attending a course, following one or several devices, a diploma course, etc.).

Start from the existing practices of people, and start by developing knowledge and skills according to and in connection with the concerns and problems of the students.

Create a department in charge of permanent researches on learning, teaching systems and educational issues posed by the educational proposals implemented within the institution, and received by the students.

… meaning paying attention to the outer world and the edges between the inner world and the outer world!

Establishing porosities and exchanges with the outside world, making encounters.

Working with all the groups surrounding the institution, and in the presence of people who want to spend time in the institution.

Inventing and tinkering with all the other educational communities in the area.

Being aware of all that is instituted (what exists and makes the institution function) while being able to try, attempt, grope and that some of these experiments become institutionalised by regularly modifying this institute.

Being aware of critical sizes: keep a small local scale (small teaching teams and small cohortes). Rather creating a cooperative network of schools than a large ocean liner.

In 1969, the Experimental University Centre of Vincennes was created by legally opening the

possibility of entering higher education for people who did not have the baccalaureate (entry pass at the time). Following the movement of May and June 1968 in France, the exams were validated almost automatically. During this period, the social significance of the university was disrupted, on the one hand by the number of applicants for higher education and on the other hand by increasing doubts about the ability of science, progress and the development of an industrial society to de facto emancipate without questioning them.

Vincennes becomes…

“The most significant institutional creation of 68, dedicated to continuing the debates, experiments and elaborations of 68 after the foreclosure introduced by the passage of the law. In this sense, in particular through the reception of non-bachelor’s graduates, Vincennes, and Vincennes alone in the university landscape, inherits—even before having started to function—an intellectual and social responsibility with regard to the school, with all the republican mystique attached to it, and not just with regard to the university. It is not the only new university created during this period, but the only resolutely opened one. To all audiences, to all questions…and at all risks.”

Legal Order of 10 November 1969 concerning the “enrollment of candidates without a baccalaureate at the Vincennes university centre for the 1969-1970 academic year”.

“Art. 1. – Candidates who do not have the baccalaureate of the second degree or a title admitted by regulation as an exemption are admitted to register for the academic year 1969-1970 at the university centre of Vincennes, subject to:

1. Satisfy the conditions laid down in article 2 of the aforementioned decree of 2 September 1969, i.e.:

Either to be twenty years old on 1 October 1969 and to justify on the same date two years of salaried professional activity giving rise to social security contributions;

or be twenty-four years old on 1 October 1969.

2. Pass the oral test of the special university entrance examinations.”

(JORF 1969, 12533)

“In order to enrol, you have to undergo an interview which is more of an individualised reception than a skills test, and prove 24 months of salaried work and 36 months in 1976. (…) Once the rule of three years of salaried employment was reluctantly accepted, the university refused to change its rules. It only added, under pressure from feminist struggles, the fact that raising a young child up to the age of three was considered the equivalent, for mothers, of salaried work” (Berger, Courtois, and Perrigault 2015, 194-5).

“Every student is an adult and every adult is considered a student among others. We will therefore simply try to create the conditions to welcome employees, by working on Saturdays and continuing the lessons every day until 10pm and even 11pm. Very quickly all the students will be mixed together. (…). This strong desire for diversity and the confrontation of students of different ages, experience and academic level was one of the keys to the pedagogy. We will speak of a university open to employees, we will welcome non-baccalaureate holders, but we will never speak of ‘young people of low level’ as we did from the time of the Barre plan [April 1977]. We will soon welcome, without any preconceived intention, a considerable number of foreign students, a large proportion of whom were themselves non-baccalaureate holders (more than 30% in some years), but without making prior knowledge of French a condition for access to Teaching Units, i.e. by pursuing the same logic of refusing to accept any prerequisites” (ibid., 191).

This welcome of non-baccalaureate students will be the object of continuous struggle with the ministry each year to allow their registration.

Motion of the General Assembly of 16 October 1974:

“The General Assembly of October 16, meeting on the initiative of the Teaching Personnel Commission, considers that the decree of September 18, 1974, which prohibits non-baccalaureate holders from preparing for the DEUGs (Diploma of that time, corresponding to the current Level 5 of the EQF), constitutes a breach of the initial contract of Vincennes, a breach of the bases on which the teachers came to this University. The General Assembly made the abrogation of this decree a matter of principle. The teachers declared that they did not accept to teach in a university where there would be two categories of students, some with the right to access national diplomas, others to whom this right would be denied.”

(Paris 8 1974)

“These particular enrolment arrangements are at the intersection of three distinct intentions. Firstly, the desire to welcome, as of right, employees: those who were pursuing a professional career, as well as those who were working to support themselves but who hoped to change jobs through their studies. In 1978, these employees represented 46% of students of French nationality, to which must be added 23% of part-time workers. Foreigners with a visa for studies do not generally take the risk of declaring themselves as workers and we therefore have no reliable statistical data.

The second intention concerned more specifically the reception of non-baccalaureate holders and reflected the desire to repair the selection made by the school system. The number of non-baccalaureate holders was approximately 10% in the first year[2], they corresponded to 34% of the student population in 1977. (…)

The third aspect was the more traditional one of democratisation and therefore access for working class students. On this last point. Vincennes did not differ much from all the other universities. (…). Vincennes was never the university of the working class, even though a close reading shows that the enrolment rate of children from the lowest categories was almost 20% higher than the national average.”

(Berger, Courtois, and Perrigault 2015, 195-6)

How to welcome students in all their diversity?

Henri Meschonnic, a teacher of linguistics and literature at the University of Paris VIII from the creation of the university centre until 1997:

“From the very beginning of Vincennes, the modern and modernist orientation of the teachers, the rejection of the classical curriculum and traditional examinations, the political conditions of its foundation, the recruitment of students mixing baccalaureate holders and non-baccalaureate holders, full-time students and salaried employees, and various age groups and motivations, meant that constantly, whatever the number of students in my course, I always saw five and even six successive levels (…). It is impossible to have a homogeneous discourse for one level, unless you reject the ‘weak’ or do nothing for the ‘strong’, chasing some or chasing others. But there are no longer any weak or strong (or they are not the ones we think they are) when there is something to look for based on the analysis of contradictions and strategies.”

“The presence of employees is not specific to Vincennes (although there are more of them than in other universities). What is specific, it seems to me, is that employees do not give up their employee status when they enter the university, that they participate in the course by contributing their personal and professional experience, and that this experience often becomes a dynamic element in the work that is done and in the communication that takes place between the different groups. Many examples could be given of the active role played by student employees in the constitution and communication of knowledge, in exchanges between students and in challenging the traditional teacher/teacher relationship. Thus, a value unit on the history of urban work will use material contributed by a postal worker or bank employee student, a course on the psychiatric institution will include nurses, a course on public finance will benefit from the contribution of a student civil servant from the Ministry of Finance, a course on the press will capitalise on the experience of computer science students, etc. (…) There is perhaps another element at play: studying at Vincennes does not appear to divide people’s lives, but rather unites and reunites them. (…)

Foreign students bring other dimensions. Their presence is one of the components of the extraordinary mix that takes place in Vincennes. In many cases, it has enabled French students to become much more directly aware of the problems of the Third World and has helped to shake them out of their Eurocentrism.”

(Debouzy 1978, 87-8)

“In the Vincennes teaching approach, there is no longer any question of ‘teaching’ or of doing nothing else but that, but of collectively ‘doing research’, and this is true from the first year onwards (…) Each student or each group of students proposes his or her own subject, his or her own field of study, and it is no longer a question of the teacher stating a body of knowledge or information which, on the day of the examination, will be required to be returned with the minimum of distortion or personal contribution. It is necessary to accompany an approach, certainly to inflect it or even correct it sometimes, in a relational structure which is no longer that of the teacher and the student but which is based on the interactive research process.”

In order to welcome these employed students, a crèche and a nursery school were also planned and set up. In the initial plans, it was talked of “a reception building (post office, bookshop, tobacco shop, travel agency, etc.) and a day-care centre with a hanging garden on the second floor.” (Paris 8 2019, 16). The opening took place on 9 and 10 December 1968, the start of the 1st academic year on 13 January 1969; the nursery school opened at the end of February 1969 and the crèche was built in March-April 1969. The latter went through several openings and closures due to continuous struggles and reorganisations (Guimier 2019).

The children were taken care by activist and voluntary parents who could also be students, and/or salaried nursery nurses, but never enough in number to meet the demands; in self-management (on the model of the 1968’s “university wilderness nurseries”) or under the aegis of the PMI (Mother and child protection). Then it stabilised in 1972 by becoming an association ruled by the 1901 law, which appointed a director in 1976.

“In January 1977, a MNEF ‘contraception, abortion, sex therapy’ will be held on the first floor”

On one hand, higher education institutions tend to recruit students “in their image”, betting that these students would be the most able to benefit from their programme and the most likely to develop the specific social and symbolic capital representing and defining the institution. On the other hand, students tend to choose educational structures according to what they perceive of them, the representations they make of them and the projection they can make of their chances of succeeding in the proposed programme, in short, by excluding structures that are a priori “not made for them.”

If they wish to change this social spiral, which appears to be a “natural selection”, institutions must first identify and then modify the social conventions that fuel it.

As the admission exam to an art school is often the first symbolic barrier to overcome, a modification of its form and expectations can, for example, contribute to a greater inclusion. In addition to free tuition, the national film school La Cine-Fabrique offers entry requirements that take the opposite view of the implicit academic expectations generally accepted for entry to schools of this type in France, effectively allowing candidates with diverse backgrounds to participate.

“Entrance Examination

The exam is not discriminating in terms of writing.

There is no scientific level required.

There is no selection based on academic record.

A candidate who does not have the A-levels or who has stopped studying can take the entrance exam.

A candidate can try to take the exam as many times as he or she wants.”

The performances offered in the artistic courses can also encourage the overcoming of the self-censorship phenomena at work in the choice of artistic courses. Recently, the Conservatoire National Supérieur d’Art Dramatique (CNSAD) has adopted a gender equality charter which removes the notion of role specialisation: gender, social origin or physical characteristics are no longer criteria for the attribution of a role.

“The elements of birth, such as the choice or refusal of an identity linked to the sex of birth, must be respected and cannot represent in any way the whole of a person’s identity. A person’s physical sex, like their sexual preferences, like their skin color, cannot, moreover, determine their overall artistic identity and restrict the educational proposals made to them.

The classical French and foreign repertoire, like the contemporary repertoire, must be freely re-examined in the light of the three preceding principles and cannot represent an eternally reproducible standard of the relations between women and men, of the place of women in society as well as in theatrical performance. Likewise, the social origin of people, such as their physical characteristics or their skin color cannot determine their ability to perform a particular task, any more than it does to interpret a particular role. The concept of role specialisation is definitely abolished.”

Extract from the CNSAD’s charter of equality:

https://cnsad.psl.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Charte-%C3%A9galit%C3%A9-Femmes-Hommes.pdf

Although it is too early to measure its impact precisely, we can bet that the symbolic place that the CNSAD occupies in the field of theatre in France will be decisive in influencing the other institutions that make up the CNSAD, which could lead to a real paradigm shift in the conception of the role of actor and to greater inclusion and visibility of the profiles that embody them.

To address the challenges faced not only by IHAE but the human societies at large, not to say Humanity, it is understood from previous statements here that IHAE had to go far beyond a definition of their role as providers of knowledge and skills to students in kind of a “costumer relationship”. In this aspect, being no more not an institution only devoted to teaching, but focused on students as searching, creating, learning artists, partners of the institution, an even more, builders of the future of humanity in those really challenging times, this requires 3 main axes for reorganising the institution:

1) An Institution for Learning

2) A supporting Institution

3) An Institution ruled by the “Ethics of Presence.”

I/ An Institution for learning

In an educational institution (e.g. higher education, but not only), students learn, i.e. build their knowledge and skills. Such building lies on the edge between two aphorisms:

the first one is from Paul Ricoeur (Hameline 1993, 15): “every self-taught person is a fraud”. One learns only from others, encountering them physically or through books, through collective experiences or traces left behind them.

the second one is from Carl Rogers: “no one has learned anything unless he has learned it himself” (Hameline 1996, 10). It is indeed the person concerned who acquires and appropriates knowledge and skills.

Therefore, an educational institution has to set up learning situations that allow a fair balance between those two aphorisms. As each one learns differently depending of the circumstances, that means setting up that balance in a variety of situations—for example: realisation projects, workshops, lectures, surveys, inquiries, observations, mutual seminars, etc.—, for an individual or in groups of various sizes, and in different time frames. That is to say that we need to multiply the procedures and situations for researching and creating together new knowledge and skills. Here, the qualification of “new” is not necessarily something new for all mankind, but simply (humbly but intensely) for a start, new for the participants.

Implementing these approaches requires considering the issues about the links and relationships between students, teachers, and the institution that hosts them. The latter must, for example: build a space for encounters and negotiations between, on the one hand, the questions, desires and issues of the students and, on the other hand, the current issues of artistic practice as analysed and presented publicly by the institution (social, political, ecological, health, economic issues, etc.).

The students are artists, i.e. practitioners in research. Some thirty years ago, Donald A. Schön highlighted the reflexive turn of professional practices with the model of the “reflective practitioner”. Many experiments today can help to bring out the notion of the researching practitioner, particularly for artists.

Adding “co-” is not just for the sake of being politically correct: it points out a requirement for the learning devices offered by the institution. Who, within the plural, participates in this “co-”, and how? This twofold question is fundamental: the other students who listen or who exchange with equal time, the teacher(s) who speak(s) without interruption or who pass through the groups to animate or relaunch the discussions, etc.

These arrangements can be based on a complex activity that each person can approach in their own way, with their own interests, and on the experiences of all those present in the institution. They allow for more socio-constructivism in the situations experienced by the students.

II/ A Supporting Institution

To build themselves as artists, the students need to face the unknown, to face their fears, those internal towards the unknown in them and those external towards the uncertainties of the “Other”, of the outer world; and doing this by going through their own experiences to discover that unknown, to face those fears, allowed to take risks, allowed to fail in unsuccessful attempts. And they can not do this if the institutions don’t allow secured space and time for that:

Secured space by a full and complete formative assessment and no more essentially based on summative assessment,

Secured time meaning that the process benefits from conditions and time to be complete (See John Dewey).

That means that the role of teachers are that of fundamental “supporters” not only permanently accompanying the students in their needs for help, but also, and essentially, in helping them identify the fields to explore, the fears to face, and to prevent them from avoiding to do so, by fear or lack of courage. That means that, of course, the learning politic of the institution is to offer many choices, opportunities for the students, but also to keep them on track within that here described process. This attitude sometimes may require the institution to impose constraints on the students, to help them not avoid the difficulties, to skip the obstacle to win. This go today against the liberal state of mind that means leaving a total choice to students.

Though, the focus of the institution’s assessment of the students needs to be on the ongoing process more than on the intermediate results, in order to assess more how the student went through his/her experiences, than what results they were able to produce in terms of quality regarding a pre-defined concept of “excellence”.

Though, the students needs more an institution and teachers as supporting facilitators than focused on providing skills and knowledge, and assessing roles.

Supporting the students in this way needs a space of confidence in which they can find themselves, grow in their qualities and strengths, and no more fear their weaknesses.

For those “new” and generalised roles, teachers need to be strongly supported by the institution,

For their own personal respect: find more satisfaction in the inner changes within a student, which is not really assessable, than delivering knowledge and skills, preparing final examinations;

For their evaluation by the institution: it is easy to assess teachers on the final successes of their students at final degree or in competitions or awards. But how assess the teachers in their rôle of mentor, facilitator? For that, it is necessary to develop a space of confidence, built through the permanent dialogue of all internal stakeholders, thus developing a “collective intelligence” (see next point). In that space that avoids any double-blind that could destroy the inner confidence of the teachers on their teaching qualities, they can develop their “new” role in total confidence that they are in line with the institution’s policy and strategy.

Supporting the teachers means creating a space of confidence in which they can totally play their role of supporting and letting the students find themselves. A space of confidence in which they can open a space of confidence for students.

As providers of confidence to teachers and students, those supporting them—heads of departments, staff and technical personnel—need to receive the same confidence and support for their roles from the institution’s authority, Board and heads of the institution.

This is possible through a total transparency of decisions, in a shared culture of collective intelligence that should rule the governance of the institution. Only through that collective intelligence will all internal stakeholders take part to the reflection on institutional missions and strategy, learning politics, then share decisions and responsibilities, thus building a true rooted quality culture which will allow improvements, transformations, creations, and provide support to those in charge of the final responsibilities, those in charge of the institution’s governance.

Supporting those in charge of the learning environment, the governance, means building a true collective intelligence through a permanent and reflective dialogue between all internal stakeholders considered as partners.

In order to support itself at its best, a higher education institution should use the principle of isomorphism as a principle of objectification and regulation of its practices. This principle can be used at several complementary levels.

The first, external one, which is the one most often implicitly at work, is to propose to students that they experience during their studies the situations they will have to face in their future lives, to take into account the external environments (social and professional) and to ask themselves in what way the curriculum they are offered will enable them to cope with them. This does not mean that the higher education institutions should strictly obey to the requirements of the job market (strict isomorphism), but should integrate into the training both the real elements of the intended professional life and the elements that make it possible to understand them, not to be trapped in them, but able to transform them, etc. (reflexive isomorphism).

The second, which is more internal, is to ensure that the form in which an institution organises its training curricula is in line with the substance that it intends to defend and to teach. During their curriculum, students live a global experience that does not dissociate form from substance. If contradictory messages appear too strongly between form and substance, the learning and the competences targeted may be compromised. To prevent this from happening, the works they follow should first of all reflect the intentions pursued in its form, and, secondly, the institution itself, in its organisation, should also embody them.

An institution seeking to develop teamwork among its students, identified as an essential professional skill to be acquired (external isomorphism), should not be satisfied with lectures on teamwork but should propose a curriculum that directly involves students in teamwork (group work, collective organisation, reflections on the notion of conflict, leadership, etc.) and should at the same time ensure that the supervising team really works as a team and that the proposed curricula result from this teamwork (internal isomorphism).

Supporting itself means, for a higher education institution, leading the regulation of its organisation by integrating reflexively the outside environment and maintaining the form/substance match through isomorphism principles.

In the ranking system spread all over the world for higher education, the value of the “inner well being of students, in the now and then and for their future” is not assessed, is not a ranking point. The double bind is not so far: of course that ideal vision is to be implemented, but in the same time, we need that ranking assessment, that defines how competitive we are, etc. That would quickly bring to a disaster…

… And all that process can not exist if not assuming and engaging in an “ethics of presence”.

III/ An Institution Ruled by the “Ethic of Presence”

Ethics is based on 3 virtues:

1. Virtue of justice in two aspects:

2. Virtue of benevolence—bene volere, willing the good—in two aspects:

3. Virtue of tactfulness: sensitivity to the other.

If definition of rules can be found for the two first virtues, the third one is totally ruled by the now and then relation between two people, two groups, etc. That is totally left to each one, but the spirit of that can be defined in that “Ethics of presence”.

Presence to oneself;

Presence to the other;

Self-presence within the presence to the other;

Self-presence of both within community, society and global world.

This is the ethics underlying the role of mentor, facilitator that the institution and teachers develop towards the students, and between themselves.

Only through that ethics of presence will the self confidence of students be possible, allowing them to be present to him or herself, and to gain trust in themselves, unique condition for a fruitful learning both from the teaching and from the experiences they will lead. Only through that ethics of presence ruling the institution will the collective intelligence within the institution reach its highest potential for the sake of the institution both at global level and for each individual.

It is therefore no longer the point of having an institution organised with levels permanently responding to the demands of higher levels (Legal authorities → Board → management → teachers → students) but to build an institution with a co-constructed interrelationship process that allows collective intelligence to operate in all possible dimensions, ruled by this ethics of presence.

These “ethics of presence” need from each one to be self transparent and honest with his own inner feelings, attitudes, deep thoughts, etc. A permanent inner and outer look is really demanding.

But reducing conflicts in the world starts by reducing conflicts in our inner space, which is the most difficult.

The challenge is really huge, possibly not achievable because it depends on the decision of each one, mainly within the institution, but with the authorities’ acceptance.

The Challenge is at the level of that for the global world today.

Check out the FAST45 art school futures scenarios!

TELL ME MOREDive into the research